At the bottom of this article is a link to a 1905 newspaper story that is quite long and detailed, but was published before Hoch was executed in 1906.

Article: “Bigamist Blue Beard Johann Otto Hoch: 50 Possible Murdered Wives,” Celebrated Criminal Cases of America, Thomas A Duke, 1910.

Johann Hoch was born in Strasburg, Germany, in 1860. His father and two brothers were ministers in Strasburg, and Johann was educated for the ministry, but he abandoned the idea and came to the United States.

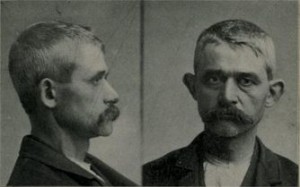

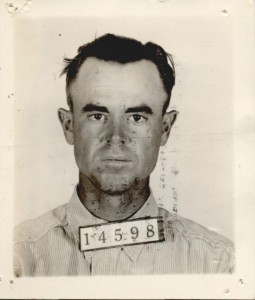

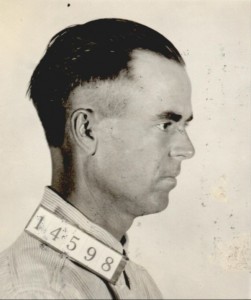

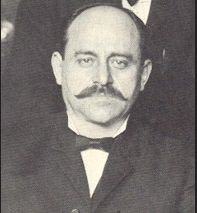

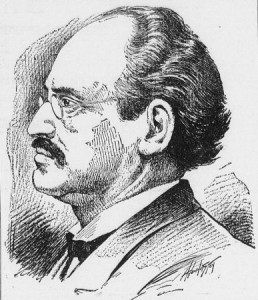

German-American Blue Beard Johann Hoch, suspected of murdering 50 wives.

Under the name of John Schmidt, Hoch married a middle-aged woman named Caroline Streicher, in Philadelphia, on October 20, 1904, but eleven days later he disappeared, and on November 9 he registered at Mrs. Kate Bowers’ hotel, 674 East Sixty-Third Street, Chicago.

On November 16, he went to the Chicago City Bank to see Mr. Vail, the owner of a vacant cottage at 6225 Union Avenue, which Hoch desired to rent. Representing himself as holding a responsible position with Armour & Co., he succeeded in procuring the cottage in which he claimed he and his wife intended to reside.

On December 3, he published an advertisement in the Chicago Abend Post, a German paper, which read as follows:

“Matrimonial—German ; own home ; wishes acquaintance of widow without children; object, matrimony. Address M 422, Abend Post.”

Marie Walcker, a hard-working woman about forty-six years of age, who had obtained a divorce from her first husband and was conducting a little candy store at 12 Willow street, saw this advertisement and requested her sister, Mrs. Bertha Sohn, to prepare and forward a letter which read as follows:

“Dear Sir:—In answer to your honorable advertisement I hereby inform you that I am a lady standing alone. I am forty-six years and have a small business, also a few hundred dollars.

“If you are in earnest I tell you I shall be. I may be seen at 12 Willow Street.

MARIE WALCKER.”

In response to the letter, Hoch called at the candy store on December 6, and during an extended conversation which followed he represented to Mrs. Walcker that his wife had been dead for two years; that he possessed $8,000, the cottage which he rented from Vail, and several vacant lots in the neighborhood of the cottage. He also claimed that his father, who lived in Germany, was 81 years of age and that when the old man died he would inherit $15,000.

It was soon agreed by the couple that they were intended for each other, and Hoch became a constant visitor at the store for the next four days, at the expiration of which time the couple decided to marry at once. The license was therefore procured and the marriage ceremony performed.

The “bride” sold her store for $75, which she gave to Hoch along with her entire savings, amounting to $350, which he claimed he needed to prepare his home for occupancy, as his money was tied up at that time.

Mrs. Walcker-Hoch had a widowed sister named Mrs. Fischer, whom Hoch met shortly after his latest marriage, and whom he learned had $893 deposited in a savings bank.

A week after the marriage, Mrs. Walcker-Hoch became very ill, and on December 20 Dr. John Reese was called in. The woman complained of excruciating pains in the abdominal regions ; she vomited freely ; had a violent thirst and a tingling sensation in the extremities, which she described as similar to ants crawling through her flesh. The doctor diagnosed the trouble as nephritis and cystitis (Bright’s disease and inflammation of the bladder).

Hoch sent for the sick woman’s sister, Mrs. Fischer, who frequently assisted about the house. She mailed her picture to her sick sister, which Hoch received, and he wrote a letter acknowledging the receipt of it, in which he stated that he intended to keep the picture himself and carry it on his breast.

Shortly afterward he accompanied Mrs. Fischer from the sick chamber to a car, and en route he told her that if he had met her four weeks sooner he would have married her. Finally Hoch and Mrs. Fischer appeared to be so friendly that the sick woman became jealous, and Mrs. Fischer left the house in a rage but she soon returned.

On January 12, 1905, Mrs. “Hoch” died, and Dr. Reese certified that death was due to nephritis and cystitis.

Mrs. Fischer was at the house at the time, and a few moments after the death occurred Hoch proposed marriage to her. She protested that the proposal was a trifle too sudden, although she accompanied him to Joliet three days after the funeral, where they were clandestinely “married.”

Hoch then suggested that the “honeymoon” be spent in Germany, reminding his “bride” of the advisability of visiting his “aged and wealthy father,” but he added that before they took the trip he would need $1,000 to straighten out his business affairs in Chicago. The “bride” volunteered to come to his assistance and she drew $750 from the bank and delivered it to Hoch.

They then proceeded to 372 Wells street, where the “bride” rented a flat and kept roomers previous to her marriage. At the door they were met by Mrs. Sauerbruch, who stated in an undertone that Mrs. Sohn, the sister who pre-pared the letter Mrs. Walcker sent to Hoch in answer to his advertisement, was in the rear of the house and had been denouncing Hoch as a murderer and swindler. The bigamist became greatly agitated and requested that he be left alone in the parlor while the two women went to the rear of the house to pacify Mrs. Sohn.

The women returned in a few moments but Hoch had disappeared. This move convinced the latest Mrs. Hoch that her sister’s suspicions were well founded, and Inspector of Police George Shippy was notified.

The body of Mrs. Walcker-Hoch was exhumed and a post-mortem examination held, which resulted in the discovery of 7.6 grains of arsenic in the stomach and 1% grains in the liver. As there was no arsenic in any of the medicines prescribed by Dr. Reese nor in the embalming fluid, the authorities became convinced, in view of Hoch’s conduct, that it was he who administered the poison. His picture was published in the papers and great publicity was given to the case.

On January 30, 1905, Mrs. Catherine Kimmerle, who con-ducted a boarding-house at 546 West Forty-seventh street, New York, notified the police that a man giving the name of Henry Bartells, but whose actions and appearance tallied with Hoch’s, was stopping at her place. Twenty minutes after he entered the house he volunteered to assist her in the kitchen by peeling potatoes, and the next day he proposed marriage, but the lady became frightened at his ardent manner of proposal.

The man was taken into custody, and after admitting that he was Hoch, claimed that he assumed the name of Bartells because of trouble he had with his sister-in-law regarding property.

When searched a fountain pen was found in his possession but there was no pen in the holder. A closer inspection revealed the fact that the reservoir contained fifty-eight grains of a powdered substance which the prisoner claimed was tooth powder, but when informed that the substance would be analyzed, he replied : “Well, it’s no use ; its arsenic which I bought with the intention of committing suicide.”

He insisted that he did not have the arsenic in Chicago and gave the location of a drug store in New York where he purchased the pen and arsenic. The police visited the store and found that fountain pens were not sold there and that no arsenic had been sold to Hoch.

By the time the prisoner was returned to Chicago, Inspector Shippy had learned of the following women who were, among Hoch’s victims :

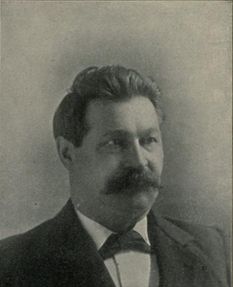

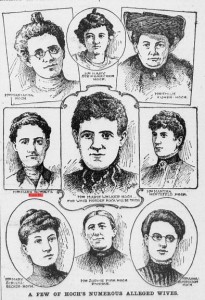

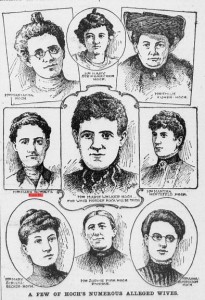

Just a few of Hoch’s wives…and victims.

Mrs. Martha Steinbucher; married to Hoch in 1895 and died four months later. When this lady was dying she declared that she had been poisoned, but it was thought that she was delirious when she made the statement and no credence was placed in it. Hoch sold her property for $4,000 and disappeared.

Mary Rankin married Hoch in November, 1895, in Chicago, and he disappeared with her money on the following day.

Martha Hertzfield married him in April, 1896, and four months later Hoch disappeared with $600 of her money.

Mary Hoch married her namesake in August, 1896, at Wheeling, W. Va., and died shortly afterward.

Barbara Brossert married him on September 22, 1896, in San Francisco, after a three days’ courtship. This lady was a widow living at 108 Langton Street. Hoch married her under the name of Schmitt and disappeared two days afterward with $1,465 of her money. As this was Mrs. Brossert’s life savings the loss so affected her that she died shortly afterward.

Hoch then took up lodgings at 30 Turk street, in the same city, and immediately attempted to creep into favor with the landlady, Mrs. H. Tannert. After a few hours’ acquaintance, he proposed marriage, but the lady refused the offer and Hoch left San Francisco.

Clara Bartel married Hoch in November, 1896, at Cincinnati, Ohio, and died three months later.

Julia Dose married this man in January, 1897, in Hamilton, Ohio, and on the day of her marriage Hoch disappeared with $700 of her money.

In April, 1898, he was arrested in Chicago for selling mortgaged furniture, and was sent to the house of correction for two years. After being liberated he began operations again as follows :

He married Anna Goehrke in November, 1901, and deserted her immediately.

Mrs. Mary Becker married Hoch on April 8, 1902, in St. Louis, and died in 1903.

Mrs. Anna Hendrickson married him on January 2, 1904, in Chicago, and eighteen days later the bridegroom disappeared with $500 of her money.

He married Lena Hoch in June, 1904, in Milwaukee, and she died three weeks later, leaving Hoch $1,500.

Then came the marriage to Caroline Streicker in Philadelphia and Mrs. Walcker and her sister, Mrs. Fischer, in Chicago, as previously related.

In addition to this list he had another wife in Germany.

Johann Hoch before or during his trial.

On his return to Chicago from New York, Hoch was interrogated at length by Inspector Shippy and then five of his former “wives” were admitted to the room for the purpose of identifying the prisoner. When they caught sight of Hoch, it required considerable effort on the part of the officials to quiet them, as they were collectively expressing their opinion of the prisoner in most vigorous terms.

On February 23, the coroner’s jury returned a verdict accusing Hoch of murdering Mrs. Walcker by means of arsenic poisoning. The case was then taken before the grand jury, where Hoch was indicted, and on May 5, 1905, he was placed on trial.

During the trial, Inspector Shippy testified that Hoch admitted to him that he had no love for any of his wives, and that when he advertised for them, he mentioned his preference for middle-aged women because it was easier to separate them from their money than younger women.

On May 19, Hoch was found guilty, and on June 3, the date for his execution was set for June 23.

He appealed to the Governor, who refused to interfere. On the day set for his execution, a Miss Cora Wilson, who conducted a furrier’s store at 66 Wabash Avenue, Chicago, came to the rescue by advancing sufficient money to make it possible for an appeal to be taken to the Supreme Court, and the Governor consented to a postponement of the execution.

Miss Wilson claimed that she had never seen Hoch, but that she desired that he be given every opportunity to prove his innocence.

After reviewing the case the Supreme Court sustained the lower court, and the execution was then set for August 25, 1905.

On August 24, he obtained another lease of life until the October session of the Supreme Court, but on December 16, this court again refused to interfere and the execution occurred on February 23, 1906.

More Reading:

“Remarkable Career of Bluebeard Hoch,” The Pennsylvania Journal, Feb. 24, 1905

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_Otto_Hoch

—###—