That Time Nevada Executed a 17 year-old, 1944

Home | Feature Stories | That Time Nevada Executed a 17 year-old, 1944This story is dedicated to ‘packerpil.’ Thank you for your continued support.

During the summer of 1942, Lafayette, Indiana, residents experienced a six-week “reign of terror” in which fifty serious and misdemeanor crimes were committed by one or more individuals.

Beginning on June 2, the crime wave included:

- Twenty counts of breaking into automobiles,

- Three counts of motor vehicle theft,

- Approximately twenty misdemeanor counts of shoplifting and petty theft (petit larceny),

- Six home & business burglaries, and

- Two counts of aggravated assault occurred during two of those burglaries.

This list does not include any affiliated counts of selling stolen property.

Around 2:30 in the morning on June 20, Mrs. Mary Soller, 72, and her sister-in-law, Emma Soller, were asleep in separate rooms when they were both awakened by someone turning on the lights to each room.

Thinking Emma was awake and needed assistance, seventy-two-year-old Mary had just stood up when a man wearing a mask threw a one-quart glass milk bottle that struck her on the left side of her head, which then careened off to hit a door frame where it shattered to pieces. She then collected two twenty–dollar bills and handed them over, satisfying the burglar, who then made his escape.

Suffering from a head injury and shock, the frail woman spent several days at a local hospital. Lafayette detectives investigating the case concluded her attacker used a common-style skeleton key to enter the home.

The next aggravated assault came on June 30 while Mrs. Francis Knoth was ironing clothes in her kitchen as her two young children slept. Since her husband worked the night shift at an industrial plant, she was startled by a noise in the front room. Thinking one of the children made the noise, she left to check on them.

As she stepped into the front room, a masked burglar accosted her. Screaming, the young man threatened to kill her with a .38 caliber revolver he had found while searching an adjacent closet. He then pushed her into another room and beat her. The intruder then ran out the front door taking the revolver and a Waltham brand watch. Also suffering from shock, Mrs. Knoth sat on the floor for several hours before she summoned the strength to scream for help. Eventually, neighbors arrived and the police were called at 12:50 a.m.

Her attacker’s description matched the description the Soller sisters had given. Local detectives were already piecing together all the separate crimes and looking for connections. Knowing Knoth’s attacker would likely try to sell the Waltham watch, they were keen to find where it would show up.

Their strategy worked, and six days later, they found a man who purchased the watch in good faith for three dollars. From him, they traced the purchase back to the seller.

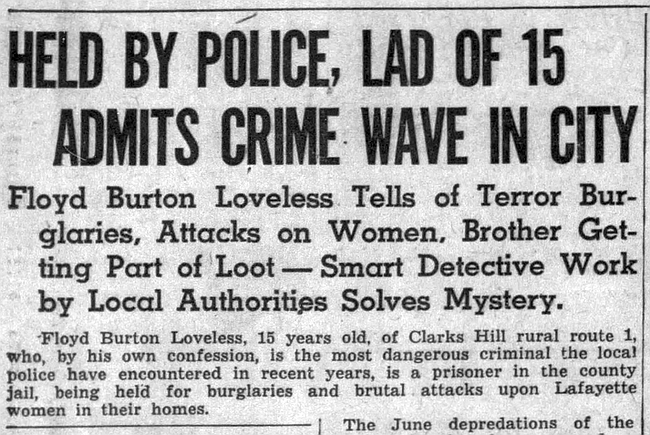

On June 7, the front page of the Lafayette Journal and Courier announced the crime wave was over with the arrest of Floyd Burton Loveless, 15, and his brother, Robert Kay Loveless, 17. When Floyd was just three, his mother Hazel, 29, stepped in front of a train on June 15, 1930. It was written up in the newspaper like it was an accident. Their father worked for the railroad and was often gone. Their grandmother raised the boys in Clarks Hill, a village fifteen miles south of Lafayette. On June 2, the boys left home for Lafayette and went on a crime spree.

No stranger to the law, both boys were already on probation for prior offenses. Seven months earlier, Floyd was placed on probation after serving nine days in jail for the burglary of a rural home near Lafayette. Robert’s probation stemmed from a 1939 conviction for motor vehicle theft. He first served time at White’s Indiana Manual Labor Institute for that crime, a punitive juvenile facility with a school and working farm.

Memories of that institution may have tapered Robert’s tolerance for crime to only fifteen misdemeanor counts of shoplifting. It was young Floyd who was Lafayette’s John Dillinger for June of 1942.

Behind bars, Floyd’s confessions trickled out of him over the next five to six days. Eventually, a polygraph examination, in which he flunked horribly, encouraged him to get it all off his chest. This included the two assaults, the burglaries, the motor vehicle thefts, and twenty counts of breaking into a parked automobile.

Tried in juvenile court first-degree burglary, Floyd Burton Loveless was given the maximum sentence allowed: commitment to the Indiana Boy’s School until he reached the age of twenty-one, sooner if the school trustees believed he had reformed.

Like most juvenile institutions in other states, IBS was a tough place. Teen boys were subjected to widespread theft, staff violence, violence by older boys, including sexual assault. However, since it was classified as a school and not a penal institution, the 1,300-acre facility did not have an impassable fence or guard towers. The only measure to prevent any boy from escaping was a locked door for their barracks-like quarters and a guard or two wandering the grounds.

Floyd entered the institution on July 15. Thirty days later, he and another boy, David Cline, 15, escaped and it took six hours before someone noticed they were gone. Situated thirty miles northeast of Indianapolis, the boys stole a car and drove west, most likely taking US 40, the fastest and easiest road to get there.

They financed their trip by burglarizing homes. Floyd found a revolver in one of them and kept it for himself. He should have left it there. Shortly, it would change his life forever.

By August 20, the two boys were near Elko, Nevada,[1] where they quarreled and decided it was best to split up. Floyd let Cline keep the Indiana car, but Cline stayed with Floyd until he had commandeered one himself. It didn’t take long before Floyd found a truck with the keys still in it. Cline drove behind him as they got back on the Victoria Highway (US Highway 40) to continue their journey to California.

Stealing the truck was Floyd’s second-biggest mistake that day. It belonged to Elmer Hill, the popular manager of the Horseshoe Ranch at nearby Dunphy. Everyone knew Elmer’s truck, and when Carlin Constable Adolph Berning learned the stolen truck was coming his way, he parked his vehicle along the highway and waited.

With Elko 23-miles east of him, Berning didn’t have long to wait. He had served as the town’s constable for twenty-six years, re-elected by the people each time since 1915. Throughout the county, he was known as a reliable lawman.

But on that day, August 20, shortly before noon, the odds were against him. He spotted Elmer’s truck, noticed someone else was driving it, and stood there until it stopped. At about that same time, the stolen car driven by Cline was also preparing to stop but drove away when the constable waved him off.

Berning walked over, opened the door and told Floyd, “He would have to take me in for being in a car I didn’t belong in,” Loveless later testified.

Not sending the danger he was in, Berning got behind the wheel, forcing Floyd to slide over to the passenger seat. He would later tell officials: “I pulled out a gun and said I wouldn’t go back with him. He grabbed the gun, and I shot him. The gun got jammed, and we started fighting, and then I pulled the trigger again, and it worked, and I drove off down the road.”

Berning collapsed on the driver’s seat, and Floyd pulled him the rest of the way into the truck. Then, with Berning slumped over in the passenger’s side, Floyd got behind the wheel and continued driving west.

Over the next few miles, Berning moaned in agony. Loveless replied that he was taking to him to a hospital.

Instead, he caught up with Cline a little further down the highway at Primeaux Station—a middle-of-nowhere gas station and rest-stop with a natural spring. Loveless abandoned the truck and jumped in the Buick, and the two drove off.

Cline later testified that when Loveless got into the car, he asked him what happened, and Floyd said he had shot the officer and left him in the truck.

Cline said nothing, drove a little further, and then exclaimed that he saw a pistol lying in the sagebrush by the side of the road. When Floyd went to look for the weapon, he drove off and left him there.

The end for Cline came about ninety miles further down the highway near Winnemucca, where a roadblock was waiting for him. Cline took the shoulder and drove around it, forcing him to take a seven-mile dirt road that was a dead end. He was trapped.

A cruiser belonging to Deputy Sheriff George Armstead pursued Cline. Riding shotgun with him was Wallace van Reed and Arthur C. Sebbas, who were running against each other to be the next sheriff of Humboldt County.

Trailing behind a thick cloud of dust, the two opposing candidates put nine bullets in Cline’s car, hoping to stop him. None did. At the end of the road, they watched as Cline discovered the dead-end, turned the car around, and sped towards them.

Setting up another roadblock at a narrow point in the road, all three got out and readied themselves. As he had done before, Cline steered for the shoulder in the hopes of driving around them. Both candidates saw this and opened up with two shotguns, shredding the windshield. Two of the 12-gauge pellets hit Cline in the cheek, and that was it for him. He was taken into custody and driven back to Elko County.

Meanwhile, an Elko County deputy sheriff found Loveless walking along the highway a few miles west of where he had abandoned the stolen truck and a gravely wounded Constable Berning, paralyzed from the neck down.

On the drive to the Elko County Jail, Loveless confessed to stealing the truck and shooting Berning, but when he met up again with Cline behind bars, he recanted his confession and refused to say anything more. Berning died from his wounds thirty-six hours later.

Elko County’s case against Loveless began in juvenile court but was soon bumped up to district court, a move that would have him tried as an adult. He was formally charged with murder on September 12, pleaded innocent on September 22, and his trial began on September 28—thirty-nine days after he mortally wounded Berning.

Jury selection lasted most of the first and second day, and by the end of business on the third day, September 30, the trial itself was over, and Loveless was found “…guilty as charged in the information.” His defense attorney had but just one strategy, avoid the death penalty. The high point of the trial was when Loveless took the stand and wept as he described shooting Constable Berning. Explaining himself as best he could, Loveless told the jury he didn’t know Berning was a law enforcement officer since he was wearing plainclothes.

Dale Cline’s actions to rid himself of Loveless and his willingness to testify against him saved him from being charged as an accomplice. He would later be taken into federal custody for interstate motor vehicle theft and “held until the age of maturity.”

According to Nevada state law, district judge James Dysart, who oversaw the case, had no choice but to sentence Loveless to death, which he did on October 5. His execution date was scheduled for December 13.

One Nevada newspaper pointed out that his sentence could later be commuted to life in prison by the state board of pardon and parole or the governor.

But it was clear from almost the beginning that that was never going to happen. From the time he was bumped from juvenile to district court to the judge sentencing him to death, Nevada newspapers, including the Reno Gazette and the Nevada State Journal, systematically lied about Floyd being sixteen-years-old. He wasn’t. He was fifteen. He would turn sixteen on November 2. They had his files. The FBI had his files. They didn’t get it wrong on accident. They never got Cline’s age wrong; he was always fifteen.

Sixteen made Floyd Loveless more of a man and less of a boy if his true age were published.

Several days after his sentencing, Loveless was transferred to the Nevada State Prison in Carson City, where he resided on death row. On November 30, two weeks before his execution date, his defense attorney, Taylor Wines, filed an appeal, something he didn’t have to do.

In his oral argument before the state supreme court, Wines rightly pointed out that his client was found guilty of murder, but the kind of murder was left out. According to section 10068 of Nevada Compiled Laws 1929, murder is not just murder. First-degree or second-degree murder must be clearly spelled out in the charges, and instructions to the jury.

“All murder which shall be perpetrated by means of poison, or lying in wait, torture, or by any other kind of willful, deliberate and premeditated killing, or which shall be committed in the perpetration, or attempt to perpetrate, any arson, rape, robbery, or burglary, * * * shall be deemed murder of the first degree; and all other kinds of murder shall be deemed murder of the second degree; and the jury before whom any person indicted (or informed against) for murder shall be tried, shall, if they find such person guilty thereof, designate by their verdict whether it be murder of the first or second degree.”

On April 21, 1943, the Nevada State Supreme Court ordered the verdict set aside and Floyd Loveless to receive a new trial.

Returning to Elko County District Court, his second trial began on November 15, 1943, and like the first one, it was over on the third day (November 17). This time, the language was clear, “…guilty of murder in the first degree.”

Loveless, now seventeen, was again sentenced to die in the Nevada gas chamber. But fortunately, a second trial also gave him the right to an appeal which his defense filed on February 29, 1944.

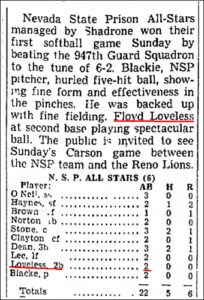

As he waited for oral arguments and the court’s decision, Floyd Loveless lost his bitterness and became a proper young man. He kept time for prison boxing matches, read books in his cell, wrote letters, embraced the Catholic faith, and played on the prison softball team. His skills as a second baseman even got his name in the sports section of the Nevada State Journal when NSP trounced the 947th Guard Squadron 6-2.

Oral arguments were heard on July 10, and the Nevada State Supreme Court published its opinion on August 16. Judgment was affirmed. Execution was scheduled for September 29, 1944.

During his last forty-four days, the state board of pardons and paroles refused to commute his sentence, and the governor declined to intervene. His attorney filed a writ of habeas corpus, claiming Loveless was insane. But this only postponed his execution from 5:00 a.m. to six o’clock that evening.

At that time, the warden read the death warrant to him, and a physician attached a stethoscope to his chest. Loveless’s last request to the warden was for roses to be sent to his grandmother back in Indiana. This was granted.

At 6:24 p.m., he was led from his cell and walked his last thirteen steps with Father Buell by his side. Although no last words were recorded, it is customary for prisoners about to be executed to ask forgiveness from all those in life they had hurt and to forgive all who sinned against them. Loveless was then strapped into a steel chair, and the doctor connected the stethoscope to monitor just outside the small cinderblock building.

At 6:27 p.m, sodium cyanide pellets were dropped into a pot of sulfuric acid, and within sixty seconds, the room filled with white poisonous smoke. Floyd took a deep breath, as he had been advised to do, and by 6:29 p.m., he was pronounced dead.

Epilogue: Although it was believed by many that he would be buried in the prison cemetery, Floyd Loveless’ body was transported back to Indiana, where he was buried next to his mother in Fairhaven Cemetery, in Mulberry, Clinton County. His father and brother were buried elsewhere.

[1] At the time, US 40 connected with the Victory Highway near the Wendover Cut-off not far from the Great Salt Lake Desert. Nevadans called it what it had always been to them, Victory Highway, while others called Highway 40, or US 40, which was constructed after the Victory highway was built. Soon, it would be neither of them as Interstate 80 was constructed in their place.

– – – -# # # – – – –

True Crime Book: Famous Crimes the World Forgot Vol II, 384 pages, Kindle just $3.99, More Amazing True Crime Stories You Never Knew About! = GOLD MEDAL WINNER, True Crime Category, 2018 Independent Publisher Awards.

---

Check Out These Popular Stories on Historical Crime Detective

Posted: Jason Lucky Morrow - Writer/Founder/Editor, February 11th, 2022 under Feature Stories.

Tags: 1940s, Execution, Juvenile, Murder, Nevada