The Kidnapping of Little Charley Ross, 1874

Story by Thomas Duke, 1910

“Celebrated Criminal Cases of America”

Part III: Cases East of The Pacific Coast

In 1874, Christian K. Ross, a wealthy and highly respected gentleman, lived with his family in their large stone mansion on East Washington Lane, in Germantown, a suburb of Philadelphia, and within its corporate limits.

At this time, his family consisted of his wife and seven children, named Stroughton, Harry, Sophia, Walter, Charley, Marian and Annie.

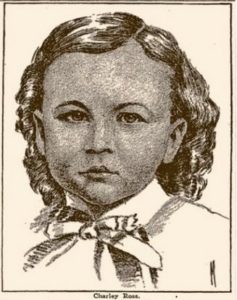

Charley Ross, who was four years of age, was a chubby little fellow with long flaxen curls, and his appearance, intelligence, and disposition made him a favorite with all who met him.

His brother, Walter, was six years old, and the two were constant companions.

On June 27, 1874, two men drove by the Ross mansion in a buggy, and seeing Charley and Walter playing on the sidewalk nearby, they stopped, and after giving the children candy, engaged them in conversation.

These men drove by each day thereafter, always conversing with the children if they were in sight.

On the afternoon of July 1, they again stopped, and Charley Ross asked them for a ride and also asked them to purchase him candy and firecrackers with which to properly celebrate the approaching “Fourth of July.” The two strangers readily agreed to comply with his requests, and Charley and Walter were taken into the wagon.

When they had proceeded some distance, Charley asked why they did not stop at some store to buy the candy, but the men told him that they would go to “Aunt Susie’s,” where they could procure a whole pocketful for 5 cents. When they reached Palmer and Richmond Streets, Walter was handed 25 cents and directed to the corner store, where firecrackers were sold. While he was making his purchases, the kidnappers drove off with Charley. When Walter came out of the store he cried loudly when he realized that he was left alone. Among the sympathizers who gathered about him was a Mr. Henry Peacock, who finally restored him to his father.

Several persons were found who had seen the wagon pass when both boys were in it, but none could be found who observed it after Walter left it, nor could any trace be found of the horse or wagon.

The motive for the abduction was not apparent at first and numerous theories were advanced. Some claimed that family troubles had caused some relative to kidnap the favorite child. Others stated that he had fallen into the hands of gypsies, while some expressed the opinion that the child was merely being concealed by Mr. Ross for the purpose of gaining notoriety.

On July 3, Mr. Ross received a letter which had been mailed in Philadelphia.

It read as follows:

“July 3—Mr. Ros : be not uneasy you son charly be all writ we is got him and no powers on earth can deliver out of our hand. you wil hav two pay us befor you git him from us, and pay us a big cent to. if you put the cops hunting for him you is only defeeting yu own end. we is got him put so no living power can gets him from us a live. if any aproch is made to his hidin place that is the signil for his instant anihilation. if you regard his lif puts no one to search for him yu money can fetch him out alive an no other existin powers. dont deceve yuself an think the detectives can git him from us for that is imposebel. you here from us in few days.”

When the contents of this letter became public the officials decided that strenuous methods must be employed. Not only in Philadelphia, but throughout the country within a radius of many miles of that city, a search was instituted, the like of which, both as regards magnitude and thoroughness, has seldom been made by American police officials. The indignation of the people in that vicinity had become so great that the officers felt safe in putting aside the technicalities of the law in reference to searching private property and unless they knew that the occupants of buildings were above suspicion, the premises were searched and any protest caused officials and neighbors to look upon the protester with suspicion.

In like manner were vessels in the stream inspected, but no trace was found of the missing child, although the thorough search resulted in an enormous amount of stolen property being recovered, and the thieves were subsequently prosecuted.

In the meantime, parents, especially of the wealthy class, had become so terrorized that they practically made prisoners of their children.

On July 6, Mr. Ross received a second letter, also mailed in Philadelphia, in which the kidnappers demanded a ransom of $20,000 and threatened to kill Charley if the detectives were put on their trail or their demand was not complied with.

The letter further stated that if Mr. Ross desired to communicate with the custodians of his child to enter a personal in the Philadelphia Ledger as follows: “Ros. we are ready to negotiate.”

On July 7, Ross replied as directed and on the same day another letter was mailed to him in which he was directed to state in a personal whether or not he would come to terms.

It was then decided to continue answering the letters and to frame the answers so as to necessitate further correspondence, as it was hoped that eventually something would be revealed by which the child could be traced, or that a blunder would be committed which would lead to the detection of the writer.

Accordingly, the answer to the last letter was: “Ros will come to terms to the best of his ability.”

On July 9, another letter was written in answer to the last personal, in which the kidnappers stated that they were growing impatient and that the reason for the evasive answer was obvious to them.

Notwithstanding the tenor of the last letter from the kidnappers, Ross continued to publish ambiguous answers, and afterwards he announced that he would not compound a felony by paying money to the monsters who committed this atrocious crime.

But when Ross noted the mental and physical condition of his wife he regretted the stand he had taken, and through the personal columns of the Ledger he expressed a desire to reopen negotiations; which brought a reply from the kidnappers, in which they chided him for his impulsive and indiscreet actions.

On July 22, Mayor Stokley, of Philadelphia, on behalf of several fellow citizens, offered a reward of $20,000 for the arrest of the kidnappers.

On ‘the same day Ross informed the kidnappers, through the usual channels, that he would comply with their request in every particular.

In reply to this the abductors expressed their reluctance to enter into any further negotiations at that time, as they claimed the moon was not at a phase for the propitious transaction of business. (The reason for this statement will appear presently.)

On July 30 the abductors instructed Ross to procure a valise and, after painting it white, to put $20,000 in small bills inside and take the train leaving at midnight for New York. He was instructed to stand on the rear platform of the last car. This train was due to arrive in New York about one hour after sunrise. He was cautioned to be on the alert from the moment the train left the depot, and if he saw a torch and a white flag waved at night time near the track or a white flag alone in the day time, he should throw the valise instantly, and if it was found to contain the money demanded, the child would be restored to its home within ten hours.

Ross procured the valise and proceeded on the journey, but instead of $20,000, the valise contained a letter in which Ross stated that he would not pay the money until he saw his child before him.

He took his position on the rear car and made the entire nerve-racking journey, but seeing no signal he returned home, where he found a letter from the kidnappers censuring him for not making the trip.

It appears that a newspaper erroneously stated that Ross had gone in another direction with some officers to follow up a clew, and believing this information came through an authentic source to the papers, the kidnappers abandoned their plans.

As the moon was not shining on the night selected, it is probable that they were waiting for a dark night so that they could not be followed, and their reason for having the valise painted white was so that it could be easily found on such a night.

Communications again passed back and forth, but Ross stated positively that the payment of the money and the delivery of the child must be simultaneous.

The response to this ultimatum was mailed in New York. The kidnappers stated that the simultaneous exchange was impossible, and they again threatened to kill the child.

On August 2, Chief of Police George Walling, of New York, telegraphed to Philadelphia for the original letters from the kidnappers, adding that he had reliable information as to their identity.

Captain Heins, of the Philadelphia police, proceeded to New York with the necessary papers, and Chief Walling’s informant identified the writing as that of William Mosher, alias Johnson.

The informant then stated that in April, 1874, Mosher and Joseph Douglas, alias Clark, endeavored to persuade him to participate in the kidnapping of one of the Vanderbilt children while the child was playing on the lawn surrounding the family residence at Throgsneck, Long Island. The child was to be held until a ransom of $50,000 was obtained, and the informant’s part of the plot would be to take the child on a small launch and keep it in seclusion until the money was received, but he declined to enter into the conspiracy.

He gave a minute description of the two men, and as he described little peculiarities about them which had not been published, but which Walter Ross readily recalled when questioned more closely, it was agreed that the information was most valuable.

It was then learned that Mosher was a boat builder by trade and a fugitive from justice at that time.

In 1871 he was arrested for burglary at Freehold, New Jersey, but escaped from jail before his trial.

After his escape, he and Douglas manufactured a moth preventive called “Mothee,” and they traveled about the country with a horse and wagon while placing the article on the market. At the time of the kidnapping, Mosher resided with his wife and four children at 235 Monroe Street, Philadelphia, and Douglas resided in the same house.

They kept their horse and wagon in a stable on Marriot lane, but the stable was torn down and the horse and wagon, which was undoubtedly the one in which Charley Ross was carried away, disappeared about the time of the kidnapping.

On August 19, Douglas, and Mosher and his family, moved to New York, where Mosher had a brother-in-law named William Westervelt, who was formerly a police officer in that city.

About this time the Pinkerton Detective Agency was called into the case and every effort was made to apprehend these two men, but as nothing had been accomplished by November 6, Mr. Ross, who had been in constant communication with the kidnappers, answered their twenty-third and last letter, which instructed him to send two relatives to New York with the necessary money and to announce two days in advance, through the personal column of the New York Herald, when they were coming, the personal to read: “Saul of Tarsus. Fifth Ave. Hotel—instant.” They also warned Ross to instruct his relatives not to leave their room in the hotel for an instant on that day.

They explained that the person calling for the package of money would be in absolute ignorance of its contents or for what purpose it was to be used, and under no conditions should the relatives converse with the messenger.

They furthermore stated that the route which the messenger would take with the money had been carefully planned so that it would be impossible for him to be followed without them knowing it, and if he was followed they would kill the child and escape. If Ross kept faith they agreed to return the child within ten hours.

Ross had finally decided to act in good faith with them, and on November 15 the following personal appeared in the New York Herald:

“Saul of Tarsus: Fifth Avenue Hotel, Wednesday, eighteenth; all day.”

On the seventeenth instant Mrs. Ross’ brother and nephew left with the money and carried out instructions, but no one appeared to claim it.

This was the last move made to negotiate with the kidnappers, and Mr. and Mrs. Ross, who had been physical wrecks for months, were on the verge of becoming mental wrecks when they learned the result of the journey.

Notwithstanding their bold front, subsequent events proved that the kidnappers knew that the police were virtually at their heels and they did not dare to come out of hiding, even for $20,000, although at the time they were on the verge of starvation.

About this time, a great many wealthy New Yorkers had their summer homes at Bay Ridge, which is on the east side of the upper bay of New York. In this locality I. H. Van Brunt occupied his permanent home, and next door his brother, Judge Van Brunt, of the New York Supreme Court, had his summer home. During the winter season the Judge closed this house, which was connected by a burglar alarm system with his brothers’ home.

At 2 o’clock on the morning of December 14, 1874, the alarm bells began to ring violently, arousing the family of the Judge’s brother.

Mr. Van Brunt, thinking that the wind might have blown open a blind, which would have caused an alarm, directed his son, Albert, to investigate. The son had proceeded but a few feet when he observed some one moving about his uncle’s mansion with a lighted candle. He hastened back to his father with this information, who immediately dressed. In the meantime, two hired men named William Scott and Herman Frank were aroused. The four men procured shotguns and revolvers and went to the house, two men being stationed at the front entrance and two at the rear. It was a cold, dark, rainy night, but the men waited patiently for nearly an hour. Finally the dark forms of two men were seen as they quietly crept up out of the cellar at the rear.

Van Brunt, Sr., called “Halt,” but the response was two pistol shots, which fortunately did no damage. Van Brunt then poured the contents of his shotgun into the foremost man, who fell with a cry of agony. The second man then fired at Van Brunt, but again fortune smiled on him. Burglar No. 2 then attempted to escape by running to the front, where he encountered Van Brunt, Jr. Here a battle ensued with the result that Burglar No. 2 dropped dead from a bullet through the body.

The burglar at the rear, although virtually torn to pieces, continued to fire as long as his ammunition lasted. The shooting aroused the entire neighborhood, and when Burglar No. 1 realized that he had but a few moments to live, he called for a drink of water, and between gasps he made the following statement :

“Men, I won’t lie to you. My name is Joseph Douglas and the man over there is William Mosher. He lives in New York, and I have no home. I am a single man and have no relatives except a brother and sister whom I have not seen for twelve years. Mosher is married and has four children. (Here he waited a moment to regain his strength, and then continued.) I have forty dollars in my pocket that I made honestly. Bury me with that.” After another pause he continued:

“Men, I am dying now and it’s no use lying. Mosher and I stole Charley Ross.

“He was then asked why he stole the child and he replied: “To make money.” He was then asked who had charge of Charley Ross, and he replied : “Mosher knows all about the boy, ask him.” They then informed him that Mosher was dead, and to prove it the latter’s body was dragged over to where Douglas was lying and a light placed near the dead man’s face. Douglas, who was growing more feeble each minute, barely whispered, “God help his poor wife and family.” He then added: “Chief Walling knows all about us and was after us, and now he has us. The child will be returned home safe and sound in a few days.”

Although the rain was falling in torrents and the dying man was drenched to the skin, he begged them not to move him or force him to talk, so an umbrella was procured and held over him. For over an hour he lay writhing in agony.

Finally he became unconscious, and fifteen minutes afterward, he was dead.

Chief Walling was notified, and he sent Detective Silleck, who had known Mosher and Douglas since childhood, to identify the bodies.

Silleck immediately recognized them, and as there was a glove on one of Mosher’s hands, he said: “Take that off and you will find a withered finger caused by the removal of a felon years before.” The glove was removed and there was the finger withered away to skin and bone.

So that young Walter Ross could not be influenced in any way, he was not informed of the tragedy, but was taken to New York for a purpose unknown to him.

When he was shown the bodies he at once recognized Mosher’s remains as those of the man who drove the wagon, and when shown the remains of Douglas, he stated he was the man who gave them candy.

Peter Callahan, who saw the children in the wagon with the men, also identified the remains. Mrs. Mosher was then located, and while she admitted that she was aware of the fact that her husband kidnapped Charley Ross, she insisted that she did not know where he was concealed.

Mr. Ross then issued a circular wherein he stated that as he was positive that the leaders in the kidnapping conspiracy had been killed, he had no desire to prosecute the parties who then had his child in custody, and that he would give $5,000 as a reward to any person who would restore his boy and no questions would be asked.

On February 25, 1875, the Legislature of Pennsylvania passed a law defining the offense of kidnapping and fixed the punishment at a fine not to exceed $10,000 and solitary confinement not to exceed 25 years, but it was specially provided that if any persons then having any kidnapped child in their possession returned such child to the most accessible sheriff or magistrate previous to March 25, 1875, such persons would be immune from punishment.

Notwithstanding the fact that the law guaranteed protection to any one who returned this child, and as an extra inducement the father offered a reward of $5000, the child was never seen again.

Mr. Ross believed that his boy was still alive, but his principal reason for arriving at this conclusion was because Westervelt, Mosher’s brother-in-law, informed him that he (Westervelt) conversed with Douglas the day before the latter’s death, and Douglas stated that Mosher was then arranging plans for the simultaneous exchange of the child and the ransom.

Mr. Ross laid great stress on Westervelt’s statement, although Chief Walling had repeatedly declared that he had conclusive evidence that the ex-policeman was aiding the kidnappers rather than the authorities.

As the lad could converse intelligently regarding his home surroundings, and, according to the kidnappers’ letters to Mr. Ross, he constantly begged them to take him home so that he could accompany his mother to the country, it was considered probable that if the lad was still alive, he would eventually have had an opportunity to make known his identity to someone who would have restored him to his home, as the case attracted world-wide attention.

—###—