Original Title:

“The Truth about Evansville’s Infamous ‘Bohannon Crime,'” by Harry R Anderson, former Evansville Police Chief, as told to Warner O. Schoyen, City Editor of Evansville Courier, True Detective Mysteries, Oct. 1930.

Want to Read This Story Later on Your Tablet?

Download PDF file of The Last Rendezvous of a Ladies Man

.

BILL BOHANNON’S STUD OF WOMEN began early. He went through numerous volumes; and he was busily engaged in turning the pages of an unauthorized edition when he was interrupted by the stabbing flames of a revolver in the dark.

Even in his college days, when he was preparing for a .successful career in law, Bill Bohannon had acquired a reputation of “having a way with women.” To this very day, near the campus of Indiana University at Bloomington, there is a trysting place that is known as “Bohannon’s Hollow.” There he had a love nest where he wooed ardently on spring nights when the full flush of youth was upon him.

Out of school, Bill Bohannon married. But he could not be a one-woman man.

Bill Bohannon

So when he came home one cool September night with two mysterious bullets in his body, the city was stirred by the buzz and hum of voices whispering, “Who is she?”

As Chief of Police of Evansville it was my business to find out the answer.

It was the night of September 14th, 1928. There was a lull at headquarters. Nothing was happening. Probably nothing would happen. But, police know, these quiet moments of cribbage games or checkers shift suddenly into gun play and startling death the next. Hours of calm change in a twinkling into swiftly lived minutes of violence or tortuous days of turbulence and unrest.

It might be such a night.

Suddenly, at 9 o’clock, words that were to stun a city crackled from the telephone. “Bohannon’s shot!”

From that moment on, for forty-eight hours, there came tense activity that fll1ds its echo even now in everyday conversation.

“Bohannon’s shot!”

Albert Felker, police reporter for the Evansville Courier, who was to play an important part in the case later, flashed the news to his city editor. His words exploded into tile mouthpiece.

That was all Felker knew then and that was all, with the exception of unimportant details, that the newspaper knew when its final edition reached the streets five hours later. The Courier, in announcing the shooting of Bohannon, told of his wounds, his pre-delirium statements, his physical condition. But it could not tell where the shooting occurred, nor why.

Nor could it tell that three other lives that night had been swept into a swirling vortex of tragedy.

William O. Bohannon, the central figure in this drama of passion and sudden death, was a successful Evansville lawyer. Well educated, well groomed, courteous, suave, he was a polished man of the world. His practice was good and growing.

He dealt in divorces mostly. Women. Bill Bohannon liked women. And-women liked Bill Bohannon.

And why not? Broad-shouldered, handsome, virile, he was at the same time mild-mannered, and had learned many soothing words and phrases in his years of dealing with women who· poured out their marital sorrows to him in the privacy of his office. And he had that appeal of near swagger, born of confidence.

Too, he was always the gallant. Had not gallantry and chivalry meant so much to Bohannon, he might still be carrying on his intrigues today.

September 14th, 1928, was a Friday. Friday nights were Bohannon’s “club” nights. His club, his wife understood, was political in nature and was secret unto holiness. Only those within its select inner circle were permitted to attend. He could not even breathe the names of its members to his wife.

At a quarter of 9 o’clock that night Mrs. Bohannon was seated in the living room of her comfortable home at 1201 Blackford Avenue enjoying a quiet chat with a friend, little knowing that tragedy at that moment was stalking at her door step.

Suddenly she thought she heard her name called. The voice, it seemed, came from afar. Surely she was mistaken. Names come that way, hauntingly, in calm, peaceful hours.

But again “Lillian!” There was no mistake this time. She opened the door and peered out.

At the curb stood her husband’s automobile, lights burning and motor idling. She thought she saw him slumped in the seat behind the wheel.

Then she heard her name called again, not more than a hoarse whisper this time. There was calmness in the tone. The gallant William Bohannon would not alarm his wife.

With a shriek, she ran to the automobile.

“Honey, I’ve been shot,” he whispered, “two hold-up men-” and his voice trailed away into incoherent mumbling. There was only to be the words, “Honey, forgive me, you have been so kind,” uttered in a lucid moment in the hospital, and then-silence.

Friends of Mrs. Bohannon came at her call and the attorney was taken to the Deaconess Hospital where I sent detectives to await any word that might issue from the operating room. Reporters also stood in restive inactivity in the silent lobby patiently waiting for a break.

All they learned was that Bohannon had been shot twice and probably fatally. One of the bullets had entered the abdomen and had emerged at the back. The other had penetrated the chest. Either was a mortal wound.

I went into consultation early. With Prosecuting Attorney E. Menzies Lindsey and Edward Sutheimer, then Chief of Detectives, we groped blindly for a lead.

Mrs. Bohannon, questioned, knew nothing. All we were sure of, with what meager facts we had been able to glean, was that it was to be a sensational case.

The shooting of a prominent, respected attorney, no matter what the circumstances, promises sensations. Especially so if that attorney is not unattractive to women, nor blind to their charms. Through the remainder of the night the real story behind the shooting was purely conjectural. Where had the shooting occurred? Surely, not far from his home. For how could any man, we reasoned, drive his automobile any distance, being so badly wounded?

We were not satisfied that in his meager explanation to his wife he had told everything. Or even the truth. Someone had cause to shoot him. But who? And why?

With the coming day, as the attorney, unconscious, fought with his powerful physique a losing fight with death at the hospital, I set the entire police department to work in solving this puzzle.

His automobile, examined as soon as we got the report, revealed no due. There was nothing to work on. Yes there was. Bohannon had come home with his vest buttoned and his coat on. Two bullets had pierced his shirt. Yet neither his coat nor vest showed any bullet holes.

He had been shot while his coat and vest were removed! Was it not a normal conclusion that he had been surprised with a woman?

Had Bohannon become too friendly with another man’s wife? Had some sweetheart of another listened too attentively to his pleadings, and then told? Had some hired assassin “taken him for a ride?”

Coroner Max Lowe, an able investigator, interested in the case, was the first to issue a postulate.

“Bohannon was out with a woman whom he wants to protect,” Lowe said. “They were parked along some lonely road near the city and were surprised by hold-up men. Bohannon resisted because he did not want the identity of the woman learned. He was shot.

“It was reasoned that the shooting occurred near the city, because of Bohannon’s physical condition. It could not have been within the city limits or someone would have heard the shots. No reports of shooting had been received at Police Headquarters.

He arrived home alone after driving-how far? Could his strength be measured in miles? Not many. We were at a loss where to attack. But we were reasonably sure that at the bottom of it all could be found a woman.

“Find that woman,” I ordered. It was a harsh assignment. It had long been whispered about and now spoken openly, that this attorney had not been a model of constancy. Surely someone must know the woman –or some woman. If anyone did, he did not come forward that night, openly.

We questioned several women who, we thought might be woven into the plot. One of these left on a train for Chicago an hour after being quizzed. All gave satisfactory accounts of themselves for the night.

As the morning wore on it became increasingly evident Bohannon was not to reveal more than he already had when he said ”I’ve been shot by two hold-up men.” His strength was leaving him rapidly. It was known that he would not survive. It was a matter of hours only, his physicians said.

At 9 o’clock that morning we got our first clue.

Detectives looking over Bohannon’s automobile on the night before had missed a clue that was to help them piece the story of the shooting together. They found, clinging to the framework underneath the car, some cornstalks.

Bohannon had been on or near some highway where he must have driven through a corn field. That meant little, then. Every highway about the city lay through corn fields. And corn stands high in Southern Indiana in mid-September.

It was baffling. It appeared that there was to be no solution unless the woman herself came forward in an effort to help identify the bandits, or the bandits themselves would tell. I t was extremely improbable that either should happen.

Detectives were sitting about mentally building up theories and blowing them to pieces again when at 10 o’clock in the morning the first real “break” came. The body of a dead man was found at the edge of a corn field about four miles from the city.

Coroner Lowe, Sheriff Shelby McDowell and I were notified. The man had been shot twice, once through the right shoulder and once squarely through the heart.

The body was found by Henry Schwartz, a farmer, at the edge of his corn field. He was driving by with a horse and wagon when he spied it, partially hidden in a ditch. It would not have been noticeable from a speeding automobile.

The road along which the gruesome find was made is known as the Lynch Road. It is four miles from the city and at that time was a popular trysting place for couples who carried secrets in their hearts. It was out of the way and not often patrolled by deputy sheriffs.

We immediately, of course, linked it with the fata wounding of Bohannon.

Bohannon always carried a gun. He was an expert in the use of firearms. I t was his hobby to collect weapons-and shoot them. Not far from where the dead man was found Bohannon had a summer home on a tract of land where he also maintained a private rifle range. Here he spent many idle hours alone, coaxing vicious barks from a revolver or automatic with a teasing trigger finger.

Did he know, perhaps, that some time he was to be in desperate need of speedy action and deadly aim?

He never was known to drive his car without a gun handy. A specially constructed holster had been built into the driver’s seat of his automobile where he could reach it easily with the minimum of suspicious movement.

Had he engaged in a gun fight with bandits, then it was almost certain that this dead man had tasted the fruit of Bohannon’s hours of pistol practice.

The body found in the ditch was that of a young man, probably twenty, probably twenty-five years old. He was of powerful physical make-up, with broad shoulders and bull-like neck.

A wrestler, perhaps, or boxer. His face, with its strong set jaws, broad ‘stub nose, and dark complexion, gave every appearance of a foreigner.

A foreigner, perhaps, of some Southern European extraction.

There are a meager few of those in Evansville.

Clutched in the dead man’s right hand was a rope. A search of the immediate vicinity revealed a flashlight and a billfold. There also was evidence of a struggle. Not far away there was a wide swath cut through the field of corn, wide enough for an automobile to pass through. The com was broken thoroughly and the path was fairly straight, indicating that the car must have been driven at an exceedingly high rate of speed.

There was no gun to be found. Bohannon’s gun had not been located although it was known that he had carried one on the night before.

But who was the dead man? Papers or letters that he might have carried were missing. There was not an identifying thing about hint.

The body was brought to the undertaking parlors of Klee and Burkhart in Evansville. Here the clothing was carefully guarded by officers who looked it over minutely for any trace of identity. His cap, a trademark revealed, had been purchased in Detroit. His suit had been bought in Chicago. A painstaking search finally revealed, indistinctly, a laundry mark.

This laundry mark was simply the letters “F. M.” While we looked upon them as being of some value, Felker, always an enterprising reporter, took it upon himself to trace the letters through the city’s laundries.

Of the more than a dozen, there were only three that used the initials of a patron’s first and last names as identification.

The first of these, Felker learned, had no customer whose name corresponded with the initials “F. M.” The second, he learned, with hopes rising, had one.

“But I know him,” the bookkeeper said. “He lives at —.” That left only one.

The last proved more promising. The letters were used for one customer. His name?

“Well, he always brought his laundry and always called for it.” They did not know his name nor his address. But he was “middle-aged, dark, and of a slightly foreign cast.”

“Middle-aged.” Felker walked away from the telephone, beaten. The man on the morgue slab still held his secret.

We were definitely certain, however, that the dead man and the wounded Bohannon had met on that Friday night. There could be no other conclusion. The tracks of the automobile that had driven through the corn field corresponded to the tread of the tires of Bohannon’s car. There were cornstalks on the framework of the auto. And a little later we learned from Mrs. Bohannon that the billfold found was the property of her husband.

Mrs. Bohannon also brought, out another fact that was to clinch the theory that her husband and the unidentified corpse had fought a duel to death. She brought forth the gun that Bohannon had carried the night before. She had found it in his automobile and had hidden it.

The gun was of the caliber that was used in the killing of the stranger. Three shots had been fired recently. Then the gun had jammed.

Bohannon’s billfold was empty. There was no money in the pockets of the dead man. In fact, they had been turned inside out. There was no money on the ground about the scene of the struggle. The absence of this important evidence pointed unmistakably to the presence of a fourth person at the trysting place, a companion of the dead man. And had not Bohannon said there were “two hold-up men?”

So, instead of one mystery that faced us when that Saturday morning broke, we now had three. Who was the dead man? Who was his companion? Who was the woman in the case? We knew that at least two of the questions had to be answered before we could hope to learn the third and last.

Meanwhile, hundreds of persons, in an endless line, the morbidly curious and those who thought by chance they might be able to recognize this mysteriously silent person, passed through the morgue. They looked at his face, shook their heads, and passed on. They paused outside to stand in sombre groups and speculate on his identity.

He looked like a wrestler, they said. Then someone remembered that there had been a wrestler with a carnival in Evansville the week before. His name was Frank Martin. “F. M.” Lorin Kiely, an attorney and a wrestling promoter, was called in.

“Well, he looks something like him, but I wouldn’t be certain.”

The carnival at that time was appearing in Hickman, Kentucky, and a long distance telephone call was placed in an effort at solution. The hopes of the authorities were doomed to failure. They were informed that the wrestler was still with the carnival and was not, so far as anyone knew, carrying any bullets in his body.

The sands of Bohannon’s hourglass of life were running low with the passing of the day and his lips remained silent. Toward dusk it appeared that the stranger was to lie unidentified throughout the night and possibly for all time.

Shortly before 5 o’clock in the afternoon Arthur B. Burkhart, the undertaker, was standing beside the form of the dead man when he heard a girl of about eighteen gasp and say. “Poor Frank.”

He seized the opportunity.

“Did you know him?”

“Yes!” She caught her breath. “He roomed with the Meadors on Harriett Street. I knew him. Frank was a good boy.”

Burkhart in his excitement failed to get her name.

At about the same time Patrolman Collison received a “hot tip” from a friend who visited the morgue.

“I didn’t know him,” Collison was told. “But I know where he lived. He has a friend at 1314 Harriett Street and lived there.”

Collison immediately relayed his information to headquarters. An investigation was under way at last with something tangible to work on.

Strangely enough, the man they were about to arrest had passed through the morgue that afternoon and had spent many minutes gazing in silence at this puzzling corpse.

His face, those who later recalled having seen him at the morgue said, revealed no clue as to the turmoil that must have raged within. As the face on the slab yielded no trace of the grimness it had known in the few tragic moments before life was snuffed out, so that face of his buddy bore a mask that was impenetrable.

Police officers going to 1314 Harriett Street were informed that the Meadors had moved that day. They now lived at 1102 Harriett Street just two blocks away.

Frank Paisley was the man arrested at the Pearson Meador home. He was twenty four years old and came from Essex, Missouri. He had, so far as we then were able to ascertain, no police record and the story he told of his connection with the dead man was not incriminating. Instead, convincingly believable.

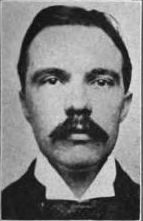

Frank Paisley

The dead man was Frank Mills, Paisley said. Mills was only nineteen years old. He came from Chicago, where he had a wife from whom he was separated. His real name was Milchunas and he was of Lithuanian parentage.

Mills and Paisley had worked together in Detroit and had come to Evansville about six weeks before, where they obtained work in a furniture factory. However, business was dull, and they had been laid off. They had not worked in two weeks.

He and Mills, he said, started out the evening before in Paisley’s automobile. In Garvin Park Mills saw a girl acquaintance and left Paisley. The latter, after riding about for a few minutes, returned to his rooming place.

There was no flaw in his story. There was nothing to attack. Paisley, the elder Meador and his son, Lee, told officers, had returned early the night before and had played cards with members of the family. There was nothing in his demeanor, they said, that might indicate any fierce mental unrest. He acted as usual, they said.

Paisley, as well as Mills who roomed with him, was a well-behaved young man, sober and industrious. Surely the police couldn’t suspect that Paisley had had anything to do with the crime, even if Mills had, which they also found it hard to believe.

Be Sure To Follow Us on Facebook for Weekly Updates, New Stories, Photos & More

We were not satisfied. Paisley was taken to Police Headquarters for further questioning. While he was there Detectives Charles Freer, Paul Newhouse, and Opal Russell went to his room, where a search revealed a revolver. With this they returned to headquarters. An examination proved that it was of the same caliber as the one with which Bohannon was shot. It had been fired recently.

Confronted with the gun, Paisley still maintained that he knew nothing of the crime. Questioning was continued, intensely, unabatingly. Within an hour he blurted out a confession.

“About 6:30 o’clock in the evening of September 14th,” Paisley’s confession started, “Frank Mills and I left our Harriett Street home in my car. We drove out State Road No. 41 and turned east about a mile north of Pigeon Creek and went east about one mile. Mills directed me to stop by the side of the road near a woods.

“Mills told me he wanted to catch a couple parked on the road and take the man out of the car and get the girl. Mills had a gun in his possession and showed it to me.

“After I had stopped the car as Mills directed he took a window cord rope about ten feet long out of his pocket. We got out of the car and down in the ditch on the south side ‘of the road. Mills cut the window cord, gave me half and kept half. Mills had his gun with him and told me to bring along the flashlight that I always carried in the car.

“We waited in the ditch one and a half or two hours and then a car drove up from the west and stopped at the side of the road near the ditch in which we were hiding and about two hundred feet west of my car.

“When Mills saw this car he said to me, ‘That’s it now.’ I do not know whether he knew the occupants of the car.

“Mills told me that he would hold the gun on the man and that I should cover him with my flashlight and tie him with the rope.

“We stooped low on our hands and feet and crawled down the ditch to the parked car. When we got to the car I went up on the right side and Mills came up from the right rear. I flashed a light in the car and saw a man and girl in the rear seat.

“They were in an embrace. I asked them what they were doing. Mills then was at the back of the car. I ordered the man to get out of the machine, saying, ‘Buddy, come out of that car.’

“The man did get out of the car on the same side I was on and next to the ditch and stood near me.

“I ordered him to put his hands behind him so I could tie him. Instead of putting his arms around behind him he started arguing with me. Mills came around from behind the car and the man turned around and faced Mills, who had him covered with a revolver. The man started arguing with Mills and Mills ordered him to face away from him so he, Mills, could tie his hands. The man started to turn around and just then it looked like he fell partly into the front door of the automobile. I think it was then that the man with the girl got his gun.

“Mills dragged the man out of the car and they both fell in the ditch. The man landed in the ditch on his back and right side. Mills landed on his feet, standing almost over him.

“Mills shot the man with his revolver while in this position and the man in the ditch shot twice at Mills and once at me. I jumped in the ditch and ran east. I heard Mills fall. I ran about ten feet in the ditch and lay down on the ground and the shot passed over me as I did so.

“I looked around and saw one man get out of the ditch and get in the car and drive away east. The car passed on the road near where I was hiding in the ditch.

“As soon as the car passed, I went back to where Mills was on the ground in the ditch on his left side. I called to him, but he did not answer. I couldn’t hear him breathe so I thought he was dead.

“I picked up Mills’ gun and started back to my car, walking along the ditch. The man with the girl had given Mills his pocketbook while he was arguing before the fight.

“He wanted to buy off Mills so he would not touch the girl. Mills gave this pocketbook to me. As I was walking down the ditch to my car I passed a culvert and threw the pocketbook and flashlight under it to get rid of them.

“Mills told the man that he wasn’t after money but wanted the girl. He had told me that he pulled these tricks before. He said it was safe because most of the time these people caught along country roads at night wouldn’t raise a yell about it for fear of publicity.”

Paisley said that he then drove to his home where he put the gun in a dresser drawer without removing the shells. The confession was signed in the presence of Coroner Lowe, Ira C. Wiltshire, now Chief of Detectives, Philip C. Gould, and attorney and friend of Bohannon, and myself. It was obtained a little after 7 o’clock, Saturday night.

At 8:55 o’clock word came from the hospital that Bohannon had died. With Mills and Bohannon dead and the identity of the woman still unknown, we had only the words of Paisley for the story of the tragedy enacted along the Lynch Road on that fatal Friday night. Paisley disclaimed knowledge of the identity of the woman. It seemed certain then that her identity would never be known.

But within the next twenty-four hours the city was to be rocked by another sensation. What happened to Bohannon and his girl companion after the shooting we pieced together in the light of evidence gathered.

Badly wounded, but with a sense of honor that probably saved the girl from shameful violence at the hands of Paisley and Mills, Bohannon drove from the scene at a furious rate of speed. He started down the road toward the Oak Hill Road. Then as he saw the Paisley automobile parked on the highway, he veered desperately to the left and cut through the corn field belonging to Schwartz.

Schwartz, who had heard the shots, had come to the field. He said Bohannon’s car cut a swath through a quarter of a mile of high corn. Then, entering a hay field, it stopped. Here Bohannon got out and removed the corn stalks that had gathered on the fenders and bumper of his automobile.

Thinking the car contained corn thieves, Schwartz called to the driver. The motor roared again and the car shot out at a breakneck pace. Schwartz fired twice with a shotgun over the car, he said.

Picture Bohannon. Already in a state of intense fear, mortally wounded, fleeing for safety, two more shots were fired at him. Had he fallen into a trap from which there was no escape? He answered the latest volley with a furious burst of speed. He turned to the right and continued through the hay field until he struck the private road leading to the Schwartz home. He drove along this road until he emerged on the Lynch Road again, some distance ahead of the bandits’ car. then, turning to the left, sped on to the Oak Hi!1 Road. Then home.

THE city was tense with excitement Sunday. On the lips of all were whispers of conjecture as to who the woman might be. There were many names mentioned. Too, there were other theories advanced in the privacy of homes and in the gossip on street corners. Had Bohannon’s slayer been paid to kill him? Did Mills know when he said, “That’s it now,” who the car’s occupants were? Was Mills a hired assassin paid by some wronged husband or outraged lover?

On the theory that Mills may have been in contact with Bohannon at some previous time, we brought Miss Norma Feuger, Bohannon’s stenographer, to the morgue to look at Mills. She had never seen him in the lawyer’s office, she said.

Norma Feuger

We were inclined to believe Paisley’s story that Mills had gone out for the purpose of rape, with robbery as a secondary motive, and that Bohannon had merely been a victim of chance.

But even to-day in Evansville when the famous “Bohannon case” is mentioned there are many ‘who believe that Bohannon died, not for what he did that night, but for previous philanderings.

Late Sunday afternoon, Felker, a reporter, hammered away at Captain of Police August Heneisen for permission to talk to the prisoner.

“He hasn’t told all,” Felker argued. “We can get a new confession out of him.” So persistent was he that finally Captain Heneisen and Felker went to the prisoner’s cell. Felker had studied the case and had convinced himself that Paisley’s confession had not been the truth.

Felker is a smooth worker. He started in on Paisley, quietly, with an assumed air of hero worship. He wanted an interview for his paper, he told Paisley, from Paisley’s own lips. Paisley listened. For the first time since his arrest he heard sympathetic words. He fell quickly into the confidential tenor of the conversation. Felker’s questions were penetrating. Carefully he noted the answers.

“But how,” Felker asked, “did it happen that Mills did the shooting when he had the rope in his hands? How could he handle a gun with both hands occupied?”

“Well, he did it,” Paisley said, hesitatingly.

Felker continued, with Captain Heneisen now and then interspersing questions.

Paisley was weakening.

“Paisley, come clean,” Captain Heneisen spoke softly, but imperatively. The prisoner hung his head.

“I killed Bohannon.”

The words were quietly spoken, but neither Captain Heneisen nor Felker doubted for a moment but that the truth was on its way out.

“I couldn’t sleep last night,” Paisley started. “I won’t be able to sleep until I get this off my chest. They might hang me, but I guess I’ve got it coming to me.”

Then his confession came, freely and without effort at concealment. He was unburdening his soul. Then he could sleep. On the whole, his story was the same that he had told the night before, but varied in its essential details.

Paisley said he wanted to commit robbery only but that Mills insisted on “getting the girl.” Paisley argued vainly against it and when Mills ordered him to tie Bohannon’s hands behind his back, he refused.

“Hell, I’ll do it myself,” he quoted Mills as saying. Mills then handed the gun to Paisley and grappled with Bohannon, with the result that they both fell into the ditch. As they got up Bohannon fell against the door of the automobile.

“I thought he was reaching for a gun,” Paisley said, “and just then Bohannon fired. Mills reeled and fell as Bohannon ‘shot again.”

Paisley then fired twice at Bohannon, he said, and then ducked, he said, just as Bohannon’s gun barked for the third time.

During the argument and shooting, Paisley said, the girl in the car was screaming at the top of her voice.

Paisley did not believe he had hit Bohannon, as the latter entered his automobile and drove off without apparent effort.

The prisoner had served in both the Navy and the Army and had become an expert pistol shot. But it was dark and his target was not clear. He fired more in self-defense than anything else, he said.

Mills, Paisley said, had engaged in numerous other cases like the one he had planned for that night, when he lived in Springfield, Illinois. He told Paisley that he and a buddy would hold up a car at some trysting place, tie the man and then attack his girl companion. He never met with much resistance, he said.

This second confession was a “break” for the newspaper. But there was another, more important “break” even then being prepared.

At 8 o’clock that night Norma Feuger, Bohannon’s stenographer, committed suicide by drinking carbolic acid!

Paisley had said he did not know the woman. He had seen her for a fleeting instant only, when he flashed his light on the couple in the rear seat of the sedan.

“She was young and she was a blond.” That was all he could say.

Norma Feuger, young and blond, was twenty, and pretty. She was gentle and quiet. No mention had been made publicly of her name, although at the time she so dramatically entered the picture Prosecutor Lindsey was out at the Bohannon home questioning Mrs. Bohannon about her.

No taint could be placed on her spotless reputation. She had been reared in the quiet little Indiana town of Gentryville, and was as peaceful and tranquil, seemingly, as the little village that holds a store of Lincoln treasure. It was at Gentryville, historians say, that Lincoln gained the nickname of “Honest Abe” while a clerk in Jones’ store.

Norma came to Evansville two years 11 before and entered business college. She had been a good student; not brilliant, but one who attended to her work and did that work conscientiously, thoroughly, and well. She had no other interests, her friends said.

To them she was known as a gentle, unassuming girl who took life more or less seriously. She had none of her own generation’s love for excitement and thrills. She neither drank nor smoked, and attended dances infrequently. She was a “girl without a date,” as her best friends described her after she had elected to pass out of life by her own hand.

Why had she, whose name had not been mentioned, who had given no reason for suspicion, projected herself so suddenly into the case by so sensationally dropping out of it?

We all accepted it as self-condemnatory. We did not say so publicly.

Let’s see what Norma was doing during those hours between the time Bohannon left his home until she swallowed poison in the kitchen of the modest little house where she lived with her widowed mother.

Bohannon left home Friday night about 7 o’clock. Norma at that time was seen by a minister friend getting on a Weinbach Avenue bus which would take her to Eighth and Main Streets. At 7:30 o’clock Bohannon had been recognized by a friend who saw him seated alone in his parked automobile near Eighth and Main Streets.

Bohannon appeared at his home at 8:45 o’clock, mortally wounded. Norma, her mother said, returned home between 8:30 and 9 o’clock. There was nothing in her demeanor, her mother said, that might indicate that she had passed through any soul-stirring experience. Her mother did not question her about where she had spent the past two hours nor did the girl offer an explanation. Norma never did speak much anyhow, so her silence was not strange.

The following day—Saturday—Miss Clarice Cummings, one of Norma’s girlfriends and her closest companion, called her by telephone. Norma seemed utterly surprised to know that her employer had been shot. But she also was depressed by the news. Surely not surprising, as she had been employed by Bohannon for more than a year. Bohannon had been interested in the girl, his wife said, and often had taken her home from his office in the evening. With Mrs. Bohannon he had taken her riding.

Norma went to the office that Saturday morning but took the afternoon off, as had been her custom. During the afternoon she called at the hospital, but was denied admittance to the attorney’s room.

In the lobby she met Mrs. Bohannon.

“Mrs. Bohannon, may I have a minute with you? I want to talk to you,” she said.

Just as the conversation was about to begin Mrs. Bohannon was called to her husband’s side. She never saw Miss Feuger again.

Norma remained at home Saturday night, depressed and moody, interested only in the outcome of Bohannon’s condition.

Sunday about noon Miss Cummings called Norma by telephone again and they went to Garvin Park, where they spent the afternoon. There they discussed the shooting and Miss Cummings even ventured a guess as to whom the woman might have been. Norma had little to say about it.

They returned home late in the afternoon. Norma, instead of remaining at home, walked to a corner drugstore, where she bought a four-ounce bottle of carbolic acid. She didn’t know what her mother wanted it for, she told the clerk. She drank a Coca Cola and then went home.

Her mother asked her if she wished something to eat.

“No, I don’t feel hungry, mother. I just had a ‘coke’,” she replied, then went to her room.

A few minutes later she returned and walked into the kitchen. There, after an instant, her mother heard her groans and rushed out to find her dying. Close against her mother’s breast, death came.

Police found, strewn about on the floor of the kitchen, tiny bits of paper containing now undecipherable writing. Another paper carried this message in Norma’s handwriting:

“I want my mother to have everything I own … Norma.”

What might the tiny bits of paper reveal?

Why had she torn that note into bits. Or had someone else destroyed it? Does someone know, today, what Norma wrote in those torturing minutes when she was laying bare her soul?

Paisley could not tell whether Norma was the girl with Bohannon. He was brought to the morgue. He looked into the face of the girl who lay there, “young and blond.” But he did not condemn the suicide. He shook his head and said, “I don’t know.”

His death was to be demanded by the State later. But he escaped the penalty of the electric chair and now is a lifer in the Indiana State Prison at Michigan City. He was brought from his cell into Circuit Court one morning, suddenly, and on a plea of guilty was sentenced to life imprisonment over the protests of Prosecutor Lindsey. Judge Charles P. Bock, who passed judgment, has said that he never will sentence a man to the electric chair.

Evansville still talks about “the Bohannon case.” And when it does, it always comes to this: Was Norma Feuger, pretty and blond twenty-year-old stenographer, the companion of William 0. Bohannon, wealthy and prominent divorce lawyer, on the night of his ride to his last romantic rendezvous? Or was Norma Feuger an innocent dupe of the fates, who, when she feared that the pointing fingers of shame and scorn might be directed at her, sought refuge in suicide? The pretty blonde took the answers with her.

Be Sure To Follow Us on Facebook for Weekly Updates, New Stories, Photos & More

—###—

Beekman Place, once one of the most exclusive addresses in Manhattan, had a curious way of making it into the tabloids in the 1930s: “SKYSCRAPER SLAYER,” “BEAUTY SLAIN IN BATHTUB” read the headlines. On Easter Sunday in 1937, the discovery of a grisly triple homicide at Beekman Place would rock the neighborhood yet again—and enthrall the nation. The young man who committed the murders would come to be known in the annals of American crime as the Mad Sculptor.

Beekman Place, once one of the most exclusive addresses in Manhattan, had a curious way of making it into the tabloids in the 1930s: “SKYSCRAPER SLAYER,” “BEAUTY SLAIN IN BATHTUB” read the headlines. On Easter Sunday in 1937, the discovery of a grisly triple homicide at Beekman Place would rock the neighborhood yet again—and enthrall the nation. The young man who committed the murders would come to be known in the annals of American crime as the Mad Sculptor.