The Astor Place Riot: Rivalry Between Dramatic Actors Leads to Riots, 22-40 People Killed

Story by Thomas Duke, 1910

“Celebrated Criminal Cases of America”

Part III: Cases East of The Pacific Coast

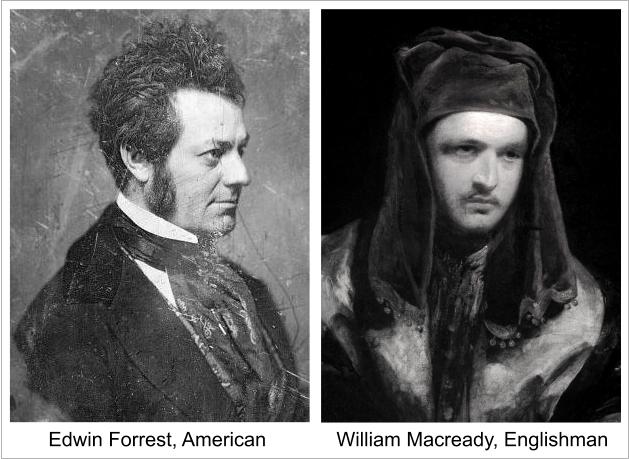

Edwin Forrest, the American tragedian, achieved his first success at the Drury Lane Theatre in London in 1827. Shortly afterward he returned to his native land, where he received continual ovations and became recognized as the foremost American tragedian.

William C. Macready, who occupied a similar position on the English stage, toured America about this time. As he and Forrest frequently appeared in the same city at the same time, there was considerable feeling of friendly rivalry, but Forrest’s tour was a great success financially while Macready’s tour was just the opposite.

Macready again toured in America in 1844. As before, Forrest and he appeared simultaneously in many cities, with the same results as on the previous tour.

Macready returned to England, and shortly afterward, Forrest, having a lively recollection of his early success at Drury Lane, made arrangements for a return engagement. When he appeared he met with a cold reception and the engagement was a financial failure.

Forrest indignantly charged that Macready’s jealousy was responsible for the change of feeling, while others claimed that Charles Dickens’s ludicrous criticisms on American customs and manners had instilled in the hearts of the English an antipathy for all Americans.

It was claimed that Macready sat in a box and hissed Forrest during a performance in England, but this was denied by Macready’s friends, who charged that while Macready was playing “Hamlet” in Edinburgh, Forrest, who was seated in a box, hissed at a portion of the performance in a most offensive manner.

Forrest soon returned to America, and in published statements bitterly denounced Macready.

The cordial welcome Forrest received on his return to America more than compensated him for the abuse he received abroad, and nightly he appeared to crowded houses.

While Forrest was in the zenith of his popularity Macready returned to America, and on Monday, May 7, 1849, he began an engagement at the Astor Place Opera House. “Macbeth” was to be played on the opening night, and Forrest, who was then playing at the Broadway, put on the same play.

The audience that greeted Forrest on this night was composed of the elite of the city, but with the exception of those occupying boxes, the scum of the city filled the Astor Place Opera House. Some were in their shirt sleeves; others were dirty and ragged, and all wore their hats. Their appearance and sullen demeanor caused the managers and players alike to become apprehensive, and after a conference it was decided to delay the raising of the curtain until Chief of Police Matsell could send a detail of officers.

The terror-stricken players then reluctantly agreed to proceed. All was comparatively quiet until Macready appeared as Macbeth during the third scene of the first act. He was greeted by a deafening and prolonged outburst of groans and hisses. As his voice was completely drowned in the uproar, he defiantly strode to the footlights and, folding his arms, he stood glaring into the faces of the ruffians, whose rage was increased by the actor’s display of contempt for them.

Finally they began to hurl rotten eggs and potatoes at the actor.

Realizing that the police detail was entirely inadequate to cope with the situation and that he would not be permitted to proceed with the performance, Macready left the stage and hastily entering a carriage which was stationed at the rear of the theater, he was driven to his hotel.

Considering that they had achieved a great victory, the mob tumbled out into the street, cheering for “Ned Forrest” as they left the theater.

This outrage was denounced by the press, and the tragedian’s calm demeanor in the face of great danger challenged the admiration of many who had previously disliked him.

Determined that Macready should not yield to this lawless element, a petition was prepared and signed by Washington Irving, Ogden Hoffman and many others, in which they guaranteed the actor protection if he would appear on Thursday evening, May 10. Macready finally consented and his ultimatum was published in the press along with a voluminous communication in which he denied that he had ever been inimical to Mr. Forrest while he was in England.

When the ruffians learned of Macready’s decision to appear again they attempted by an organized movement to prevent it. A few hours before the performance that portion of the city where the rough element congregated was flooded with circulars which read as follows:

“SHALL AMERICANS OR ENGLISH RULE IN THIS CITY?

“THE CREW OF A BRITISH STEAMER HAVE THREATENED ALL AMERICANS WHO SHALL DARE TO OFFER THEIR OPINIONS THIS NIGHT AT THE ENGLISH ARISTOCRATIC OPERA HOUSE!

“WORKING MEN! FREEMEN! STAND UP TO YOUR LAWFUL RIGHTS.”

As this circular was designed to stir up the hatred of the poor against the rich, and the Americans against the English, it was feared that serious results would follow. A heavy detail of police in civilian dress was distributed throughout the theater, and a large force of uniformed officers was detailed to preserve order outside. The militia was also held in readiness at the Armory.

For the purpose of keeping undesirables out of the theater, prominent citizens purchased great numbers of tickets and distributed them among their friends. Notwithstanding these precautions, many of the ruffians, who were well dressed for the occasion, procured tickets, and when Macready appeared they began to hiss and groan, but the officers sprang up in all directions and promptly dragged the hoodlums into a room provided for the purpose, amid the thunderous applause of the better element. The play then proceeded to the end without interruption.

But a very different condition existed on the streets in the vicinity. The mob had gradually increased to thousands. They began to throw stones at the police, who were so greatly outnumbered that they became powerless and the militia was ordered to the scene. When they arrived, the great mob became more demonstrative. Finally they located a pile of street cobble stones, which they began to hurl at the militia, some of whom sustained serious injury.

After firing into the air without any effect, except to make the ruffians more ugly, the command was given to fire at the mob, and it was promptly obeyed. Rioters fell in all directions and some who were wounded were trampled to death by the hoodlums who stampeded for shelter. In a very short while, the streets were deserted by all but the troops and the police.

Twenty-two dead bodies were removed and thirty of those wounded were conveyed to the hospitals, but as many of the dead and dying were carried away by their friends, it was never definitely known how many were killed or wounded.

It was learned that the chief instigator of the riot was E. C. Judson, alias Ned Buntline, who edited a sheet called “Buntline’s Own.” Of the sixty rioters arrested ten were indicted.

On September 29, 1849, Buntline was sentenced by Judge Daly of the Court of General Sessions to one year’s imprisonment at Blackwell’s Island and $250 fine.

—###—