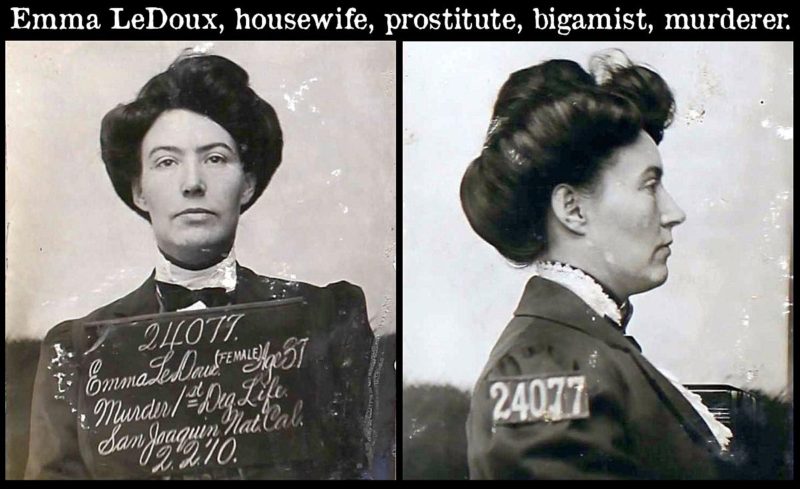

Emma LeDoux, Housewife, Prostitute, Bigamist, Murderess

Story by Thomas Duke, 1910

“Celebrated Criminal Cases of America”

Part II: Pacific Coast Cases

Emma Head was born near Jackson, Amador County, where her parents were in comfortable circumstances.

While quite young, she married a man named Barrett, but after living with him a short time in Fresno, Cal., a divorce was granted, and she then married a man named Williams, with whom she went to Arizona.

The woman had his life heavily insured and shortly afterward he died under peculiar circumstances.

In September 1902, she was married to Albert N. McVicar in Bisbee, Arizona, by Rev. H. W. Studley.

They soon separated and she finally became an inmate of a brothel.

Without being legally separated from McVicar, she married one Eugene LeDoux in Woodland, Cal., on August 12, 1905, and the couple resided at her mother’s home near Jackson.

Without being legally separated from McVicar, she married one Eugene LeDoux in Woodland, Cal., on August 12, 1905, and the couple resided at her mother’s home near Jackson.

In the meantime, McVicar had obtained employment at the Rawhide mine in Jamestown, Toulumne County, and on March 11, 1906, he met the so-called “Mrs. LeDoux” in Stockton, Cal., by appointment. Being ignorant of the woman’s bigamous relationship with LeDoux, McVicar went to the California Hotel with her and registered as “A.N. McVicar and wife.”

The next day the couple purchased considerable furniture from Bruener’s store in Stockton and ordered it shipped to Jamestown.

On the following day they came to San Francisco and proceeded to the Lexington Hotel, 212 Eddy Street, from where Mrs. “LeDoux” telephoned to Bruener’s requesting that the shipment of the furniture to Jamestown be delayed.

On the evening of their arrival at the Lexington, McVicar became ill and the woman sent for Dr. John Dillon, who diagnosed the ailment as ptomain poisoning. He administered antidotes and the patient recovered. The next day “Mrs. LeDoux” called upon the doctor and requested him to procure some morphin for her as she claimed she was addicted to the use of the drug.

Dillon provided her with a vial filled with half-grain morphine tablets.

On March 15, the couple went to Jamestown where McVicar was employed.

They registered at a hotel as “McVicar and wife” and in conversing with McVicar’s friends the woman stated that they intended to make that town their permanent home.

McVicar went back to his place of employment, but a few days later, on March 21, he quit work and drew from the company all the money due him, amounting to $163.

As a reason for his sudden change of plans, McVicar stated that his wife had persuaded him to accept a position as superintendent of her mother’s farming operations, which would be a far more lucrative occupation.

On March 23, the couple went to Stockton, where they called at Breuner’s furniture store and purchased additional furniture, which was ordered shipped to the home of her mother; but at the suggestion of the woman it was consigned to Eugene LeDoux, her “brother-in-law.”

McVicar and wife then proceeded to the California Hotel. That evening, McVicar purchased three flasks of whisky and the couple was seen going to their room at 9:15 p.m.

The next morning “Mrs. LeDoux” went to the store conducted by D. S. Rosenbaum and purchased a trunk, which she ordered delivered to room 97, California Hotel.

Shortly afterward she met an expressman named Charles Berry and requested him to call at her room for the trunk in time for the 1 o’clock train.

The woman then went to G. H. Shaw’s hardware store where she purchased some rope to “tie up a trunk filled with dishes” from a salesman named Bee Hart. When he delivered the rope he jokingly said: “Be careful you don’t hang yourself,” to which she laughingly replied that she would “be careful.”

At 12:15 p. m., Mrs. LeDoux notified Berry, the expressman, that she would not be ready at 1 o’clock, but for him to call at 2 p. m. and take the trunk to the depot.

She sent a telegram to Joseph Healy, a young plumber, residing at 1152 Florida Street, San Francisco, requesting him to meet her that evening at the Royal House, 126 Eddy Street, San Francisco.[1]

After sending this telegram the woman repaired to her room, where she packed the trunk and bound it with the newly purchased rope, and leaving it for the expressman, she went to the depot.

At 2 p. m. Berry called for the trunk, but as it was very heavy he called upon one Joe Dougherty to assist him.

When Berry arrived at the depot he met the woman, who in the meantime had displayed considerable uneasiness because of the non-arrival of the trunk, and was at the moment of its arrival attempting to telephone to the California Hotel concerning it.

The trunk was put on the baggage car of the train leaving at 4 p. m. for San Francisco, but as the baggage master noticed that it bore no check or other identification mark it was placed back on the depot truck.

In the evening it was placed in the baggage room, but in handling it the baggage man’s suspicion was aroused by the peculiar thumping sound when he turned the trunk over. Upon investigating further he believed he detected an odor similar to that of a human body.

The police were notified, and when the trunk was broken open the body of a man was found. •

This discovery created great excitement and the press all over the State gave much publicity to the case.

The body, which was entirely dressed with the exception of coat and shoes, was soon identified as the remains of McVicar, and it was found that death was due to morphine poisoning and asphyxiation.

The day after the body was found, Detective Ed. Gibson, of San Francisco, learned that Mrs. LeDoux met Joe Healy in San Francisco. He located the young man, from whom he obtained a statement substantially as follows :

“I received a telegram from the so-called Mrs. LeDoux and I met her at the Royal House as she requested.

“I knew that she had married McVicar, but she told me last night that he had recently died an ‘easy’ death and she had shipped his body to his brother in Colorado.

“When I read the paper this morning and learned that McVicar’s body was found in a trunk last night at Stockton, I showed her the article and she told me that she would go to Stockton immediately. She purchased her ticket and I accompanied her as far as Point Richmond this morning.”

Gibson then had all stations on the way to Stockton notified by telegraph and it was learned that the woman left the train at Antioch, Contra Costa County, and proceeded to the Arlington Hotel, where she registered as Mrs. Jones.

She was taken in custody by Constable Whelehan, and McVicar’s watch and chain were found in her possession.

When she was returned to Stockton she made a statement substantially as follows:

“McVicar and one Joe Miller were drinking in our room on the night of March 23d, and Miller put poison in the glass from which McVicar drank. The latter soon became unconscious and died.

“Fearing that I might be accused of the murder, I assisted Miller to put the body in the trunk. Miller and I then left for San Francisco and he also accompanied me from that city to Point Richmond.”

All the evidence tended to prove that “Mrs. LeDoux” alone committed the murder and that her statement regarding Joe Miller was a myth.

Dr. Dillon, who furnished the morphine; the salesmen who sold the furniture, trunk and rope; the expressman, baggage man, hotel attachees and Joe Healy testified before the Grand Jury, and the woman was indicted on April 2.

As it was evident that the defendant had no intention of taking McVicar to her mother’s home, where LeDoux was staying, it was the theory of the prosecution that McVicar was about to discover his wife’s bigamous relations with LeDoux and that she decided to gain possession of all of McVicar’s money to purchase the furniture which she expected to eventually use in the house she and LeDoux occupied, and then prevent the impending expose by forever sealing McVicar’s lips.

On April 17th her trial began before a jury. She was found guilty and sentenced to be hanged, but an appeal was taken to the Supreme Court.

During the empanelment of the jury the court directed an order to the Sheriff for a special venire for 75 men. Upon the return of the venire the panel was challenged by the defendant’s attorney on the ground that the Sheriff was prejudiced and had expressed an opinion that the defendant was guilty and was also actively assisting the prosecution.

As the trial judge refused to allow the challenge, the Supreme Court held that he erred and a new trial was granted.

The second trial was set for January 26, 1910, but on that morning the following letter to her attorney, Charles H. Fairall, was made public:

“Dear Sir : Owing to the condition of my health, which has become badly shattered by four years of confinement, I do not feel able to stand the strain of another trial.

“I therefore have decided to plead guilty, and I want you to do what you can to dispose of the matter quickly.

“Yours sincerely,

MRS. EMMA LEDOUX.”

Her attorney made an eloquent plea for leniency, and Judge W. B. Nutter sentenced her to life imprisonment.

[1] Healy first met this woman in San Francisco, in January, 1904, when she represented herself to be a single woman named Emma Williams. He fell madly in love with her and as she promised to marry him he presented her with a diamond engagement ring.

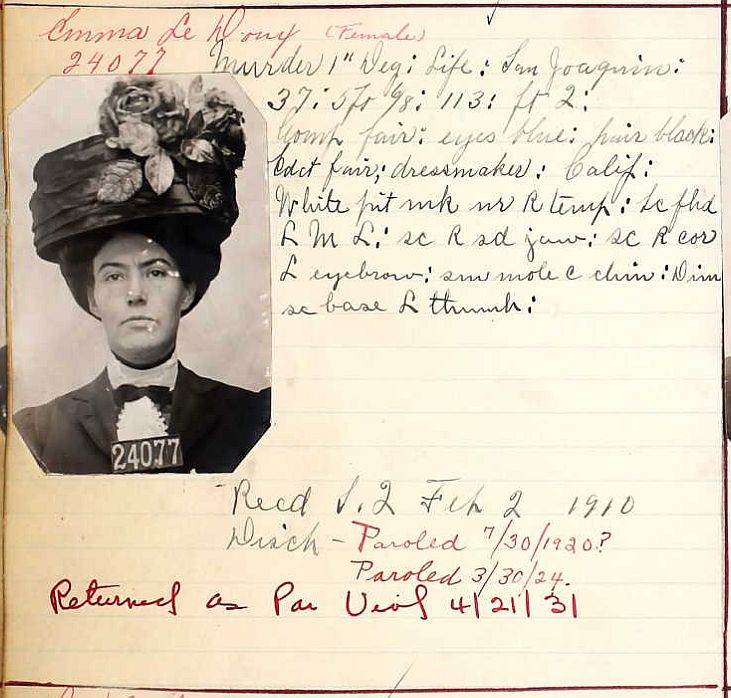

Editors Note: According to her prison records available through Ancestry.com, Emma LeDoux was paroled in 1920, returned to prison in 1921, paroled a second time in 1924, and again returned to prison in 1931. She died in prison on July 6, 1941.

The trunk she used to dispose of her husband is on display at the Stockton Museum and can be seen online. The story of her life and crimes is also available on that page, and it provides some interesting information regarding her life after she was first paroled in 1920. Apparently, she really liked booze and men, and was something of a cougar.