Dr. Milton Bowers, Wife Killer

Story by Thomas Duke, 1910

“Celebrated Criminal Cases of America”

Part I: San Francisco Cases

Milton Bowers was born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1843 and at the age of sixteen he went to Berlin to study medicine, but not as a matriculated student.

[Note: Milton Bowers is not related to Martha Bowers who murdered her husband in 1903].

In 1863, he returned to America and served in the Civil War. In 1865 he settled in Chicago, where he married Miss Fannie Hammet, who died very mysteriously in 1873. (Victim #1)

Shortly after her death, Bowers proceeded to Brooklyn, N. Y., where he married Thresa Shirk, a remarkably clever and beautiful actress who had been his patient in Chicago. As Bowers was in poor health, the couple came to San Francisco by steamer, arriving in July, 1874.

On January 29, 1881, Thresa Shirk Bowers died at the Palace Hotel and there were many circumstances in connection with her death which were never satisfactorily explained. (Victim #2)

In 1852, a wedding between J. Benhayon and a widow was celebrated in Germany. The widow had a little baby girl named Cecelia. In 1854 a boy was born and was named Henry Benhayon. The family then came to San Francisco and after several unsuccessful business ventures, Benhayon finally became a traveling salesman.

Cecelia married a man named Sylvian Levy, and a little daughter was born and named Tillie. Shortly afterward, Levy procured a divorce from his wife, who bore an unenviable reputation.

On July 19, 1881, less than six months after his second wife died, Bowers married Cecelia Benhayon Levy. In public, Bowers was most assiduous in his attentions to each of his wives, but in his home life it was claimed that he was brutal. Knowing his reputation in this respect, Mrs. Benhayon was bitterly opposed to the marriage, and it resulted in an estrangement between the bride and her relatives, which continued until a few months previous to Mrs. Bowers’ death.

In July, 1885, Mrs. Bowers’ face and body began to swell until she assumed such an extraordinary aspect that her own mother hardly recognized her, and she suffered excruciating pains, especially during frequent convulsions.

Mrs. Bowers took out life insurance policies in favor of her husband amounting to $17,000, among which was a policy for $5,000 from the American Legion of Honor. On October 28, 1885, a stranger entered the office of this order and inquired of Grand Secretary Burton if he could inspect the membership list of the various local councils of the order. Upon being informed that such a list could not be procured, he stated, after much hesitation, that a woman was sick who was a member of the order; that foul play was going on and that she would die in a few days. He then departed without disclosing his identity.

On November 2 another mysterious man hastily entered the Coroner’s office and announced that Mrs. Dr. J. Milton Bowers had just died at the “Arcade House,” 930 Market Street, and that there were suspicious circumstances surrounding her death, which should be officially investigated. After imparting this information he vanished as though the earth had swallowed him. (Victim #3).

The Coroner, Dr. C. C. O’Donnell, proceeded at once to the place and found Mrs. Bowers’ body in the same room with Dr. Bowers. He informed Bowers of the rumors afloat and the latter, with characteristic coolness, stated that the funeral would take place on the following afternoon, and that if an investigation was decided upon it should be made immediately so as not to interfere with the services. As Bowers claimed his wife died from abscess of the liver, six physicians performed an autopsy, and they decided that she had not died from that ailment. Other physicians made an examination, some of whom stated that some of the symptoms and conditions usually present in cases of phosphorus poisoning, were present in this case.

The dead woman’s stomach was removed and traces of phosphorus were found by Dr. W. D. Johnson, professor of chemistry at Cooper Medical College. It was said that Bowers received this poison in the form of samples from manufacturing chemists, but all these samples, which Bowers admitted having received, disappeared mysteriously from his office shortly after the investigation began.

Mrs. Benhayon, the mother of the dead woman, stated that when she first visited her daughter after their estrangement, it was apparent that she could not live, and she expressed this opinion to Dr. Bowers, who informed her that Cecelia was recovering and he added that he had so much confidence in his judgment that he had made preliminary arrangements to take her on a nice trip to the country. As the days passed by, Mrs. Benhayon lost faith in Bowers’ ability as a physician and she stated that it was only after repeated solicitations that he consented to call in Dr. W. H. Bruner.

After a month’s experience, Mrs. Bowers’ relatives lost faith in Bruner and Dr. Martin of Oakland was substituted. After Martin was called in, the only noticeable change in the patient was in her complexion, which assumed a beautiful and clear appearance. As her sufferings seemed to increase rather than diminish, it was suspected that arsenic had been administered. Mrs. Benhayon furthermore said:

“On the Sunday before Cecelia died, her aunt and cousin called at Mrs. Bowers’ request. I admitted them into the sick chamber, unknown to the doctor, but he rushed in and excitedly exclaimed : ‘You must get out of here ; I allow no one to see my wife,’ and he almost forcibly put them out. Although Bowers has $17,000 insurance on his wife’s life, he has refused to have any policy made out in favor of her daughter by her first husband, and when medicines were brought to the house, he usually examined them privately and then administered them himself.”

Drs. Bruner and Martin, who treated Mrs. Bowers, stated that from what Dr. Bowers had told them of the history of the case, and from their own observations, they also believed that she was suffering from abscess of the liver and treated her accordingly.

On November 12, 1885, the coroner’s jury found that Mrs. Bowers came to her death by phosphorus poisoning, and Bowers was at once taken into custody by Detective Robert Hogan, and charged with the murder of his wife.

On March 8, 1886, Bowers’ trial began before Judge Murphy of the Superior Court. Eugene Duprey, who afterwards defended Durrant, acted as special prosecutor. In his opening statement to the jury he stated that he expected to prove that Mrs. Zeissing, who nursed Mrs. Bowers, had shown unmistakable indications of being in collusion with the prisoner, and he accused Theresa Farrell, Bowers’ housekeeper, who afterward married John Dimmig, of attempting to shield Bowers. He claimed that before the death of his wife, Bowers had made arrangements to marry a woman from San Jose, and that she had already prepared her trousseau. He furthermore stated that Bowers had courted his last wife before the death of the second one.

Bowers’ record in Chicago had been obtained from the Chief of Police of that city, and the prosecuting attorney asked permission to read it to the jury, but an objection from Bowers’ attorney was, of course, sustained. The defendant was also charged with being a professional abortionist.

The case was finally submitted to the jury at 4:15 p. m., April 23, 1886, and at 9 p. m. the jury returned a verdict of guilty of murder in the first degree.

On June 2, 1886, Bowers was sentenced to be hanged, but the case was appealed to the Supreme Court. This Court was not entirely satisfied with the sufficiency of the evidence against Bowers and handed down a decision ordering a new trial. Shortly before this decision was handed down the most remarkable feature of the case occurred.

The Mysterious Death of Henry Benhayon

(Victim #4?)

Henry Benhayon, Mrs. Cecelia Bowers’ half-brother, was apprenticed to a stone cutter in Sacramento when he was about fifteen years of age, and although he became an expert at an early age, he tired of the work and accompanied his family to San Francisco. He then became “stage struck” and took lessons in elocution. He recited at lodge meetings and amateur entertainments and showed a predilection for the powerful, villain type of recitation. He once appeared in “Richard III,” but realizing that he was an utter failure, he made no further attempts in that direction. After this he sought no permanent employment, but lived off of Mrs. Bowers and his mother a great deal of the time.

On Sunday, October 23, 1887, the Coroner was notified that the body of a dead man had been found in room 21 of a lodging-house located at 22 Geary Street. The officials proceeded at once to the place and the landlady, Mrs. Higgson, conducted them to the room and on the bed the body of a young man apparently about 27 years old was found. He was laid out as though prepared for a coffin, and the bed clothing was in no manner disturbed. The landlady said that she had never seen the man before.

Shortly afterward the remains were identified as those of Henry Benhayon, the brother of the late Mrs. Bowers. Three bottles were found in the room, one containing whiskey, one chloroform liniment and a third cyanide of potassium with the label removed; all bottles being corked.

Three letters were also found in the room, one being addressed to the San Francisco Chronicle, which read as follows:

To the Editor of the Chronicle:

Sir: Enclosed find $1.00 to pay for this advertisement and the balance as a reward. I will call in a few days.

Yours truly,

Oct. 21, 1887.

HENRY BENHAYON.”

The advertisement read as follows :

“Lost, Oct. 20th, near the City Hall, a memorandum book with a letter. A liberal reward will be paid if left at this office.”

The second letter was addressed to Dr. Bowers, who was still confined in the County Jail awaiting the decision of the Supreme Court on his appeal for a new trial. It read as follows :

City, Oct. 22, 1887.

Dr. J. Milton Bowers :

I only ask that you do not molest my mother. Tillie is not responsible for my acts and I have made all reparation in my power.

I likewise caution you against some of your friends, who knew Cecelia only as a husband should.

Among them are C. M. McLennan and others whose names I cannot think of now, but you will find some more when the memorandum book is found. Farewell.

Yours,

H. BENHAYON.

The third letter, addressed to the Coroner and headed “Confession,” created a sensation. It read as follows:

The history of the tragedy commenced after my sister married Dr. Bowers.

I had reasons to believe that he would leave her soon, as they always quarreled, and on one occasion she told me that she would poison him before she would permit him to leave her.

I said in jest, ‘Have him insured.’

She said ‘alright,’ but Bowers objected for a long time, but finally said : ‘If it will keep you out of mischief, alright, go ahead.’

They both joined several lodges and I got the stuff ready to dispose of him, but my sister would not listen to the proposition and threatened to expose me.

After my sister got sick, I felt an irresistible impulse to use the stuff on her and finish him afterward. I would then become administrator for my little niece, Tillie, and would then have the benefit of the insurance.

I think it was on Friday, November 24, 1885, that I took one capsule out of her pill-box and filled it with two kinds of poison. I didn’t think Bowers could get into any trouble as the person who gave me the poison told me it would leave no trace in the stomach. This person committed suicide before the trial, and as it might implicate others if I mention his name I will close the tragedy.

H. BENHAYON.

P. S. I took Dr. Bowers’ money out of his desk when my sister died.

Handwriting experts were at once put to work on the letters and they were divided in opinion as to whether they were genuine or forgeries.

Mrs. Higgson stated that on October 18 a young man called at her house and signified his desire to rent room 21, in which Benhayon’s body was found, but the landlady stated that the room was occupied, and although she offered him other rooms, he desired only this particular one.

On the following day another man called and asked for the same room, but Mrs. Higgson informed him that while it was at that time occupied it would be vacated Saturday. He would not look at any other room, but offered to pay a deposit of $5 on that room with the understanding that he could occupy it Saturday. She accepted the money and gave him a key. On Sunday she entered the room with the pass key and found Benhayon’s body.

An autopsy showed that his death was caused by being poisoned with cyanide of potassium.

The identity of the person who engaged the room was never learned, but the man who called on the 18th inst. was positively identified as John Dimmig, who married Bowers’ housekeeper, Theresa Farrell, who was accused by the prosecution in the Bowers case with committing perjury in the defendant’s behalf.

Mrs. Dimmig, accompanied by Mrs. Zeissing, Mrs. Bowers’ former nurse, frequently visited Bowers at the County Jail.

Dimmig was born in Ohio, where he learned the drug business, but later he moved to Texas and worked as a cattle herder. Later he came to San Francisco and obtained employment at a drug store at Eleventh and Mission Streets, but finally became a book agent.

When Captain of Detectives Lees and Detective Robert Hogan asked Dimmig if he had made inquiry for room 21 at 22 Geary Street, he admitted that he had, although he had a home on Minna Street. When asked why he tried to engage the room he replied : “Well, it was a stall. I was trying to sell books.” But when Captain Lees told him that he did not believe his story, Dimmig said that he wanted the room for the purpose of meeting a woman from San Jose there. He stated that he only knew the woman by the name of “Timkins,” and that she wrote to him asking that he engage a room for Saturday night, but he added that he had destroyed the letter. He denied delegating any one to procure the room for him and did not explain why he wanted that particular room. He stated that he was under the influence of liquor on the night following the day he attempted to procure this room, and that he probably met Benhayon and incidentally mentioned the room.

Dimmig stated that he did not meet the “Timkins” woman at any place on Saturday evening, and claimed that he could not understand how Benhayon gained admission to the room which he, Dimmig, was so anxious to rent.

Dimmig then handed Captain Lees a letter which was addressed to him (Dimmig) at The Western Perfumery Co., 26 Second Street, and which read as follows:

“City, Oct. 22, 1887.

“J. A. Dimmig,

“Sir :—Call on me at once. I am in a devilish fix. I don’t want your money but your advice. I think it is all up with me. You will find me at Room 21, No. 22 Geary Street. “HENRY BENHAYON.”

Notwithstanding the remarkable coincidence that this letter indicated that Benhayon was occupying the same room Dimmig inquired for, the latter stated that he paid no attention to it and when it was submitted to the handwriting experts they disagreed as to its genuineness.

Although Dimmig was not in the habit of having his mail sent to the Western Perfumery Company, he called at this establishment shortly after this letter arrived to learn if there was any mail there for him.

Captain Lees stated that Dimmig had obtained twenty-five grains of cyanide of potassium at the drug store of Dr. Lacy and tried to procure it at several other drug stores but failed.

Detective Hogan stated that when first questioned on the subject, Dimmig denied having purchased any of this poison.

Another singular coincidence in connection with the location of the room where Benhayon’s body was found, was that Mrs. Zeissing roomed at Morton and Grant Avenue, and the back entrance to the scene of the tragedy was only a few feet away. The Benhayons stated that there was an intense hatred between her and the dead man.

Louis Goldburg stated that some weeks previous he met Benhayon and accompanied him to a room at 873% Market Street, where Benhayon stated he was doing some writing for a book agent. As Benhayon was a slow and poor writer it seemed singular that he should be employed in that line of work, unless it might be for the purpose of obtaining specimens of his handwriting. Dimmig admitted having a room on Market Street but he stated that he forgot the number.

On the Saturday afternoon preceding his death, Benhayon made arrangements to visit a dentist on the following Monday, and he had also purchased tickets to take his little niece, Tillie, to the theater on Sunday night.

No one was produced who could show that Benhayon had even attempted to purchase any deadly poison. Assuming that he did commit suicide his reason for so doing was never made clear.

If the alleged confession was genuine, his voluntary statement regarding Mrs. Bowers’ character would indicate that it was not done through a desire to expiate that crime, and in speaking confidentially to friends shortly before his death, Benhayon expressed a firm belief in Bowers’ guilt and also expressed the greatest hatred for him.

It was not apparent that he had any reason to believe that his guilt would be discovered, nor is it probable that the lost memorandum book contained anything of an incriminating nature when he contemplated offering such a trivial reward for its return.

Benhayon was last seen alive at 11 p. m. on Saturday night when he appeared to be in an intoxicated or drugged condition. He was accompanied by a man and woman, yet these two persons never appeared to explain where or under what circumstances they left him.

Four witnesses testified that on the Friday evening preceding the death of Benhayon, Dimmig entered Dewing’s Bush Street book store to purchase some books for Mrs. Zeissing, and that he then had a flask of whisky similar to that found by Benhayon’s body.

On November 12 Captain Lees charged Dimmig with the murder of Benhayon. The defendant made repeated efforts to be released on a writ of habeas corpus, but failed.

During this trial a prosecution was begun for criminal libel against Loring Pickering, of the San Francisco Call, because of an editorial published on November 13 in regard to Dimmig’s wife.

On December 10 Judge Hornblower held Dimmig to answer before the Superior Court. In doing so, Hornblower attached considerable importance to the fact that the testimony showed that Dimmig called at the Western Perfumery

Company to learn if any message had been left for him, and upon being handed the letter with a special delivery stamp on it, which was alleged to have been sent by Benhayon, he took no further action, although he carefully preserved it, contrary to his usual custom, but did not notify the police of having received it until they called to interrogate him regarding his efforts to procure the room in which Benhayon’s body was found.

On February 20, 1888, Dimmig’s trial in the Superior Court began before Judge Murphy, and on March 14 the jury disagreed after deliberating sixteen hours.

His second trial began before the same judge on December JO, 1888, and after deliberating twenty-three hours the jury acquitted him.

As some of the handwriting experts swore that the Benhayon “confession” was genuine, so far as the handwriting was concerned, the District Attorney, believing that it would be impossible to convict Bowers again, consented to his dis-charge. He resumed his practice in San Francisco and shortly afterward married Miss Bird of San Jose. They apparently lived happily together until his death in 1904.

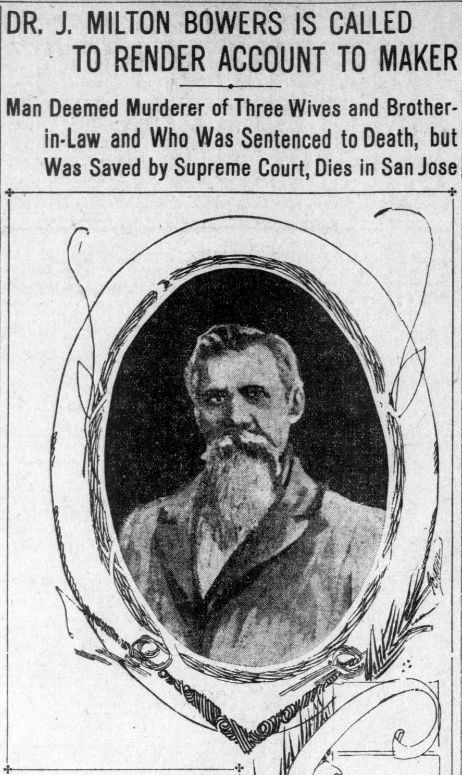

Dr. Milton Bowers, from his 1904 Obituary notice in the San Francisco Call

See Also:

San Francisco’s Weirdest Murder Case, SFGate.com

Celebrated Criminal Cases of America, by Thomas Duke, 1910