The Career of Conman and Forger, George Bidwell, 1835-1899

Story by Thomas Duke, 1910

“Celebrated Criminal Cases of America”

Part III: Cases East of The Pacific Coast

George Bidwell was born in New York State about 1835. His parents were very strict Methodists and the children were not permitted to play on Sundays. Bidwell Sr., met with financial reverses, and when George reached the age of 12 years, he conducted a small street stand, from which he sold various articles and supported the family. He saved enough money to enable him to take his father into partnership with him in Grand Rapids in 1849, and they gradually became prosperous merchants. Through mismanagement they failed in 1854, and young Bidwell even disposed of his jewelry to pay his debts. At the age of 23 he went to New York and gradually became very successful as a marketing agent for different grocery concerns. In 1858 he married an estimable young lady and supported his family beside.

He left his place of employment shortly after his marriage, and almost immediately afterward received a letter from a former customer in which he was informed that the customer had been asked to pay a balance of $10, which he had already paid to Bidwell, who gave him a receipt at the time. The customer also informed Bidwell’s former employers that he had paid the money, and they at once became suspicious and refused to accept Bidwell’s explanation that it was an oversight.

They refused to accept the money from Bidwell, but had him arrested for embezzlement. When the circumstances were explained to the magistrate, he was discharged. This experience, however, injured Bidwell’s standing in the business community, and although he made several attempts to establish himself in New York, he met with no success. In 1864, he invented a steam kettle from which he made several thousand dollars. With this money he opened a wholesale confectionery business in Toronto, but failed in this. As his family was not with him, he spent his evenings around billiard parlors, where he became acquainted with a man who gave the name of Frank Kibbe, and who confided to Bidwell that $1000 was due him through a business transaction ; but as he feared to call for it through fear of being arrested by his creditors, he agreed to give Bidwell $500 if he would get the money, which he did.

Kibbe, seeing that he could trust Bidwell, finally persuaded him to go to Providence, R. I., where they opened a swindling commission house, and by gradually gaining the confidence of the wholesalers they accumulated a large stock. Finally Kibbe persuaded Bidwell to go to New York in the “interest” of the firm, and when he returned he found that Kibbe had sold the entire stock at a discount and departed with the $20,000 he had obtained. Bidwell traced him to Buffalo, where he forced Kibbe to disgorge $10,500.

Bidwell then returned to New York and was attracted by a sign, “Partner wanted with $5000.” He made inquiry and a man who called himself Dr. S. Bolivar stated that he had $5000 and was looking for a reliable partner with a like amount so that they might purchase a prosperous grocery business.

Bidwell expressed a willingness to provide the money if the facts were as represented. He sent a friend to the store who learned that the entire business was for sale for $5000 and that the doctor was evidently trying to swindle him out of his money. He then confided to the doctor that he had been engaged in the same “graft” himself, and they had a hearty laugh.

These men evidently concluded that they were well matched, for they formed a partnership and opened up another swindling commercial house in Wheeling, W. Va., under assumed names, but business became so good that they regretted they had not used their own names and operated a legitimate business. Their operations at this place, in July, 1865, caused their arrest and conviction on a charge of conspiracy to defraud. While incarcerated, a jailbreak occurred and four escaped, but one prisoner, named Morgan, was killed by the guards while making the attempt.

Bidwell was sentenced to serve two years, and as it was his first conviction he longed for his liberty and regretted that he had not escaped with his fellow criminals. He and another prisoner procured a knife and after notching the edges, used it as a saw and were about to escape when they were betrayed. They were not discouraged, and on the following Christmas they made good their escape while the guards were full of “Yuletide cheer.”

Bidwell then went to New York, and although he attempted to pass some paper which had been forged by one Wilkes, he was unsuccessful.

He then met a forger named George Engle, who was known as the “Terror of Wall Street,” and after gathering in a few thousand dollars from forged paper, they left for England in 1872, accompanied by Bidwell’s brother, Austin, and George McDonald. McDonald was a Harvard graduate and his mother, a most estimable lady, accompanied him to the dock, believing that he was going abroad to become a cotton merchant.

Arriving in London, George Bidwell purchased a letter of credit from the London and Westminster Bank under the name of Hooker, and procuring some of the bank’s letterheads, he sent forged letters of introduction, purporting to be signed by the manager of the bank, to several of the leading banks in Europe. He also mailed letters to himself which were enclosed in the London bank’s envelopes and addressed to him in care of the banks he intended to swindle. He then left for Bordeaux, France, and proceeded at once to the bank, asked for his mail, and on the strength of the letter of introduction already in the bank’s possession, he was accorded every courtesy. He presented a forged check for 50,000 francs, which was paid after a slight delay, and he departed. He proceeded immediately to Marseilles, and visited the bank of Brune & Co., where the same modus operandi was employed which proved so successful on the preceding day; the only difference being that on this occasion 62,000 francs were obtained. The next day found him at Lyons, where he obtained 60,000 francs in identically the same manner. He then returned to his confederates in London.

As all of this money was in French notes, they immediately changed it to English gold before the fraud was discovered.

It was then determined to send Bidwell to South America and Engle prepared a forged letter of credit, but as the name of the sub-manager of the bank was omitted, the trip was a failure from a financial standpoint, as Bidwell only obtained £10,000, Brazilian currency, on a forged check. He then returned to Paris, where he joined his companions. Shortly afterward, George Bidwell went to Amsterdam, and while learning the banking system in vogue there, gained possession of a bill on Baring Bros., which he forwarded to his confederate, McDonald, who was in London.

Shortly afterward Bidwell received a dispatch from McDonald as follows:

“London, November 2, 1872.

“George Bidwell, Amsterdam:

“Have made a great discovery. Come immediately.

“MAC.”

Bidwell returned to London at once, but the “great discovery” did not appeal to him, although it suggested a plan which eventually resulted in the great Bank of England forgery.

When the party first reached London from America, Austin Bidwell deposited about £1500 in the Bank of England under the name of “Warren,” and did not draw on it until December 2, 1873.

On this date he deposited £1300 with the Continental Bank under the name of C. J. Horton and transferred his “Warren” account in the Bank of England to this bank, and then began to draw or deposit almost daily to create the impression that he was a business man. He then purchased several bills of exchange, which were also taken to this bank, and it was while handling these bills that it was discovered that the Bank of England was careless in investigating the genuineness of the signatures thereon.

Bidwell then cabled for one Noyes in New York, whom he intended to use in the work at hand. Noyes went to London, and without being taken into the details of the conspiracy, blindly obeyed orders and remained loyal to the end.

On December 28, 1872, Bidwell sent genuine bills of exchange amounting to £4307 to the Bank of England for discount, and as it was done without hesitation, he became thoroughly convinced that the signatures were not properly investigated.

On January 21, 1873, George Bidwell began operating on the Bank of England by forwarding £4250 in false exchange bills to be placed to the credit of “Warren,” which was the name under which his brother Austin had opened his account. In a few days a courteous note addressed to “Mr. Warren” was received which stated that the request had been complied with.

George Bidwell then sent Noyes to the Continental Bank with a “Warren” check for £4000 to be placed to Horton’s credit, and in a few days Noyes presented Horton checks for £3000 and purchased United States bonds with the money.

This completed the operation, which was repeated at intervals until they feared that the frequent purchase of United States bonds by Noyes would attract attention. He therefore changed his practice by presenting the checks as before, but instead of purchasing bonds, he drew the money.

Neither McDonald nor Bidwell ever appeared near the banks, and as their success had been phenomenal, they now having $300,000 in bonds and several thousand in cash, they decided that they would make a final scoop and quit.

Accordingly, on February 27, Bidwell sent about £25,000 in false bills to the Bank of England in the usual manner and received the .usual courteous note in acknowledgement. Through carelessness, Bidwell neglected to put the date of acceptance on two of the bills, and this proved to be his fatal error. The bank clerk looked upon this as a mere oversight, and on March 1, 1873, the bills were sent to B. W. Blydenstein, the supposed acceptor, who at once declared them to be forgeries. This discovery was kept quiet, and a few days afterward Bidwell sent Noyes to the Continental Bank with the usual style of check, but for the unusual amount of £,20,000.

Noyes was placed under arrest at the bank and taken to the Bow Street Station. He passed Bidwell while en route, but pretended not to recognize him.

During the operations, McDonald and Bidwell occupied quarters at aristocratic St. James Place, Piccadilly, where the bills were made. When the arrest was made Bidwell burned up the blocks and, as he thought, all incriminating evidence, but as McDonald was in the act of writing a letter at the time, he told Bidwell to save a piece of blotting paper.

The arrest and expose created a great sensation. McDonald and Bidwell became alarmed and made a fatal mistake by suddenly moving to other quarters before their rent was due. The landlady then recalled the mysterious actions of these men while under her observations, and as it was published that Noyes came from America and the landlady knew her two gentlemen-of-leisure boarders came from the same country, she went to their former lodgings, but all she found was the little piece of blotting paper, which she took to the police station. McDonald fled to New York and Bidwell fled to Ireland, but was thunderstruck, when in Cork, he picked up a paper announcing a large reward for the arrest of George Bidwell. The circular stated that all out-going ships and railroad stations were under surveillance and that Bidwell had been traced to Ireland. This fact was given great publicity, and as every man, woman and child had the reward in mind, he was kept constantly on the alert and was eyed with suspicion at every turn.

He then fled to Edinburgh, Scotland, arriving on March 10, 1873, and remaining until April 3, at which time he was arrested because of a clew given the police by a newsdealer where Bidwell bought papers daily. This dealer noted that this man had an American accent and his description tallied with that of the one published of Bidwell.

The police trailed the man to his lodgings, where the landlady referred to him as “mysterious acting.” Upon refusing to give an account of himself he was arrested, and taken to the Bow Street Station in London.

Austin Bidwell, instead of going to America, as previously agreed upon, went to Havana. He was brought back to London on May 28. It was claimed that a woman whom McDonald had associated with, gave the police valuable information as to the direction in which the fugitives fled. (Continues below image.)

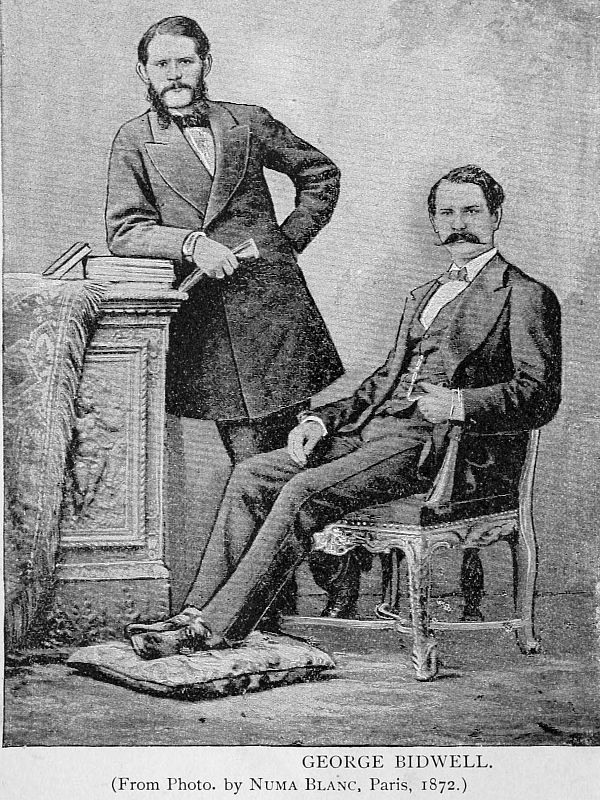

Austin Bidwell, standing, and George Bidwell, seated.

Austin Bidwell, standing, and George Bidwell, seated.

McDonald was arrested when his steamer reached New York Harbor and his United States bonds, $10,000 in gold and precious stones of an equal value were taken from him. McDonald employed able counsel and a great effort was made to prevent his extradition on the ground of insufficiency of evidence. His points were not well taken and he was returned to London. After considerable delay the trial on one of sixteen indictments was set for August, 1873.

During the trial it developed that while these men had demonstrated that as cunning criminals they had few equals, yet they did what the commonest criminal nearly always does, that is, leave a trail behind upon which a shrewd detective could pile up a mountain of evidence.

To begin with, it will be recalled that while George Bidwell was destroying the evidence of their crimes in their rooms just previous to their flight, McDonald, who was writing. a letter at the time, asked him not to destroy the blotter, as he desired to blot his letter and envelope. It was supposed that Austin Bidwell had gone to New York, and this letter was addressed to him there and the impression of the name and ad-, dress was left on the blotter, which could be plainly read by holding it to the mirror. They even used this blotter while preparing their forged bills and the forged names could also be plainly discerned.

They sent a box to New York addressed to Major George Matthews, which contained $220,920 worth of United States bonds which were purchased at the Continental Bank by Noyes. This box was seized by the New York police. It was proved that this box was shipped by McDonald on March 5 under the name of Charles Lossing. Attorney Charles DaCosta of New York testified that he was present when the box was opened in New York and that it also contained some of George Bid-well’s jewelry. In addition to this evidence, the man who gave the box to McDonald was produced. The detectives also found a London directory in the defendant’s room from which a part of a page had been torn, and on obtaining a similar directory it was found that the portion of the page missing contained the names of London engravers.

Five of these engravers identified George Bidwell as the man for whom they had engraved the blocks which were used in printing the bills.

While being chased through Ireland, Bidwell boastfully wrote to McDonald, addressing the mail to New York, of his success in outwitting the Irish police, and enclosed the newspaper clipping announcing the reward for his capture. This letter was addressed to general delivery and was recovered and used against him. Noyes and Bidwell planned to keep their acquaintance a secret, but several witnesses were produced who had seen them holding mysterious conferences.

Mrs. Ann Thomas testified that Austin Bidwell roomed in her home, located at 21 Enfield Road, and that George Bidwell and McDonald frequently called, giving assumed names. She furthermore stated that Austin received packages which were addressed to a “Mr. Warren.”

A jeweler also testified that he sold jewelry to Austin under that name.

Before the case was submitted, McDonald made an eloquent plea in behalf of Austin Bidwell, and called attention to alleged extenuating circumstances in his case.

The jury, after deliberating fifteen minutes, returned a verdict of guilty against the four prisoners, and the judge forthwith fixed their punishment at life imprisonment.

While imprisoned, George Bidwell’s health failed, and in a fit of despondency, he attempted to commit suicide by cutting his throat. He lost consciousness through loss of blood, but recovered.

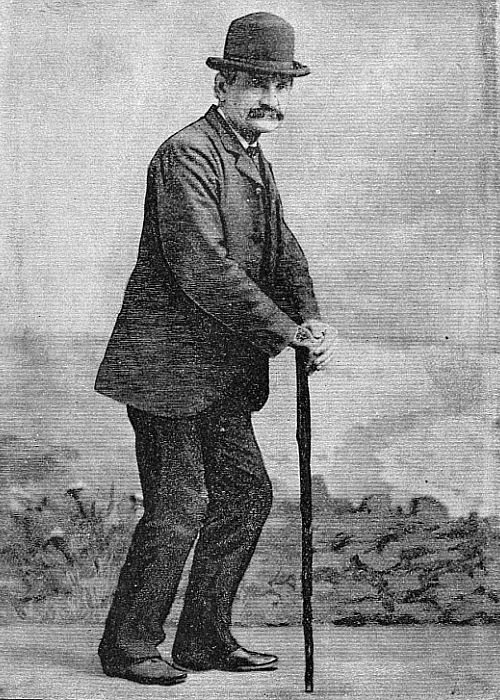

On July 18, 1887, George was released from prison because of ill health. He immediately returned to America and wrote a book called “Forging His Chains,” which dealt with his life. Later he took his sister to London, where, by constant effort, they succeeded in procuring Austin’s pardon in 1892.

George Bidwell, shortly after his release from prison.

George Bidwell, shortly after his release from prison.

In March, 1899, the two brothers went to Butte, Mont. Austin was taken sick and died on March 7. George delivered a lecture on his life in an effort to obtain enough money to bury his brother.

As he only sold fifty tickets, he became extremely melancholy, but resolved to raise the necessary money by making personal appeals to different citizens.

From lack of nourishment, due to poverty, he was now a tottering wreck of his former self, and while begging for money he slipped and fell, injuring his leg so that he was confined to his bed in his lodging-house. On March 25 the clerk found him dead in the same bed in which Austin had died a few weeks before.

An autopsy showed that he died from natural causes, but there is no doubt but that his brother’s death, and his own failure to procure sufficient money to properly inter the remains, contributed materially toward shortening the life of this remarkable character, who had fraudulently obtained over $1,000,000 during his career.

While in the English prison he composed the following, verse:

‘Tis fourteen years since on me freedom smiled, While banished far from country, wife and child;

Misfortune’s arrows sharp have pierced my heart,

My spirit, too, with most envenomed dart. In solitude wild fancies thronging,

The heart for home is ever longing.

Then heed the captive’s cry and set me free, Almighty God of Grace—if God there be.

—###—